Dear Fellow Shareholders,

I begin this letter with a sense of gratitude and pride about JPMorgan Chase that has only grown stronger over the course of the last decade. Ours is an exceptional company with an extraordinary heritage and a promising future.

Throughout a period of profound political and economic change around the world, our company has been steadfast in our dedication to the clients, communities and countries we serve while earning a fair return for our shareholders.

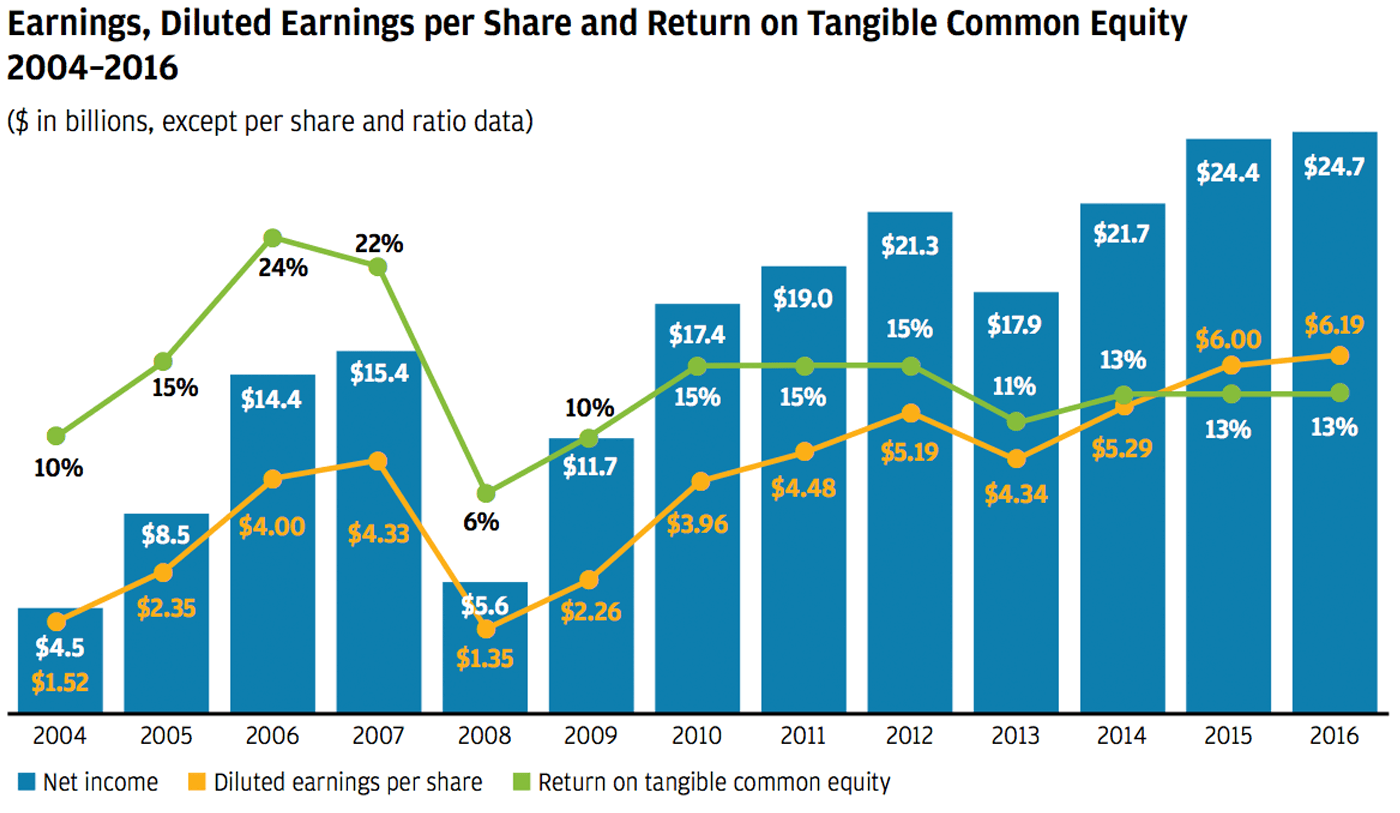

2016 was another breakthrough year for our company. We earned a record $24.7 billion in net income on revenuefootnote1 of $99.1 billion, reflecting strong underlying performance across our businesses. We have delivered record results in six out of the last seven years, and we hope to continue to deliver in the future.

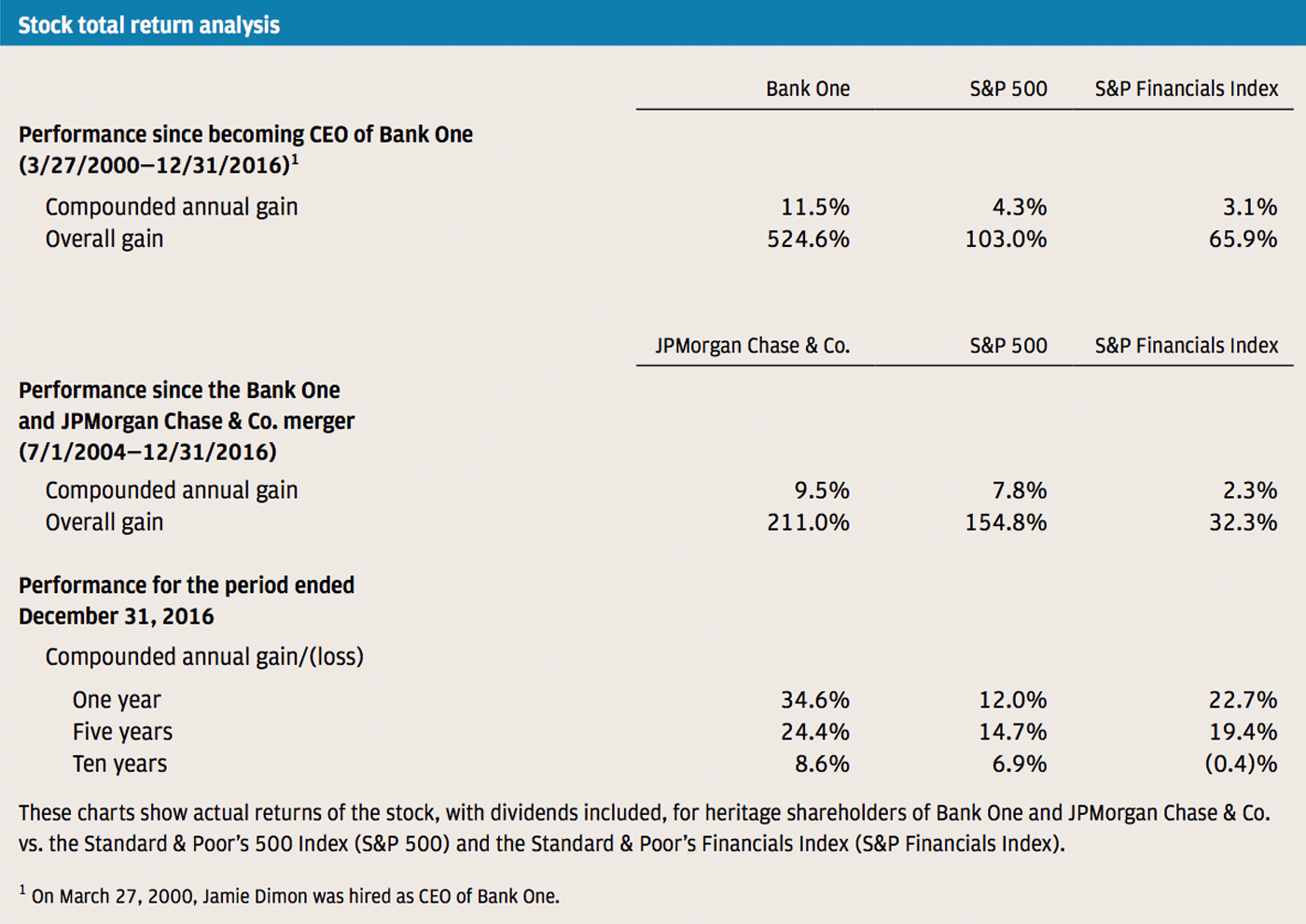

Our stock price is a measure of the progress we have made over the years. This progress is a function of continually making important investments, in good times and not so good times, to build our capabilities — people, systems and products. These investments drive the future prospects of our company and position it to grow and prosper for decades. Whether looking back over five years, 10 years or since the Bank One/JPMorgan Chase merger (approximately 12 years ago), our stock has significantly outperformed the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 and the S&P Financials Index. And this is during a time of unprecedented challenges for banks — both the Great Recession and the extraordinarily difficult legal, regulatory and political environments that followed. We have long contended that these factors explained why bank stock price/earnings ratios were appropriately depressed. And we believe the anticipated reversal of many negatives and the expectation of a more business-friendly environment, coupled with our sustained, strong business results, are among the reasons our stock price has done so well this past year.

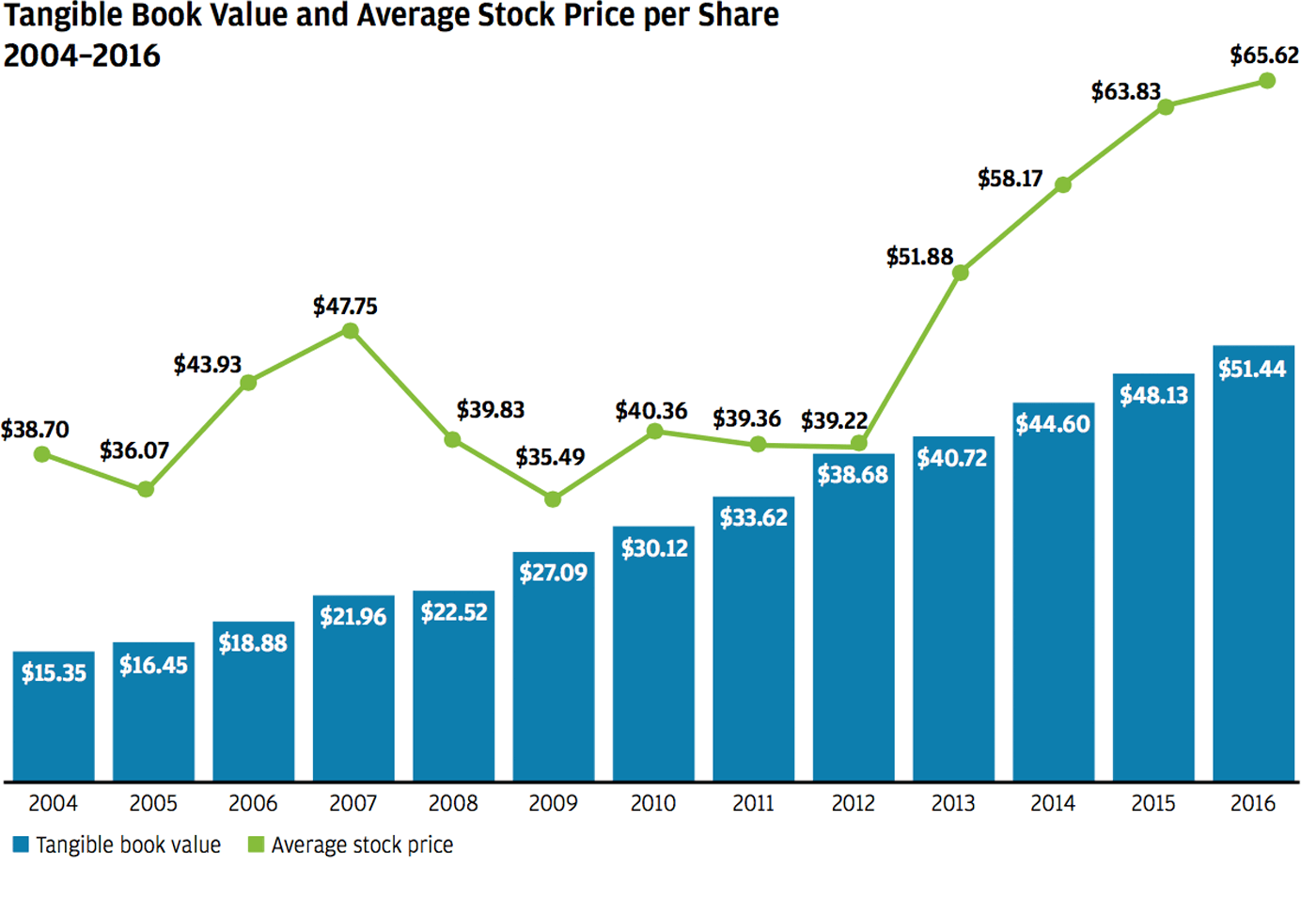

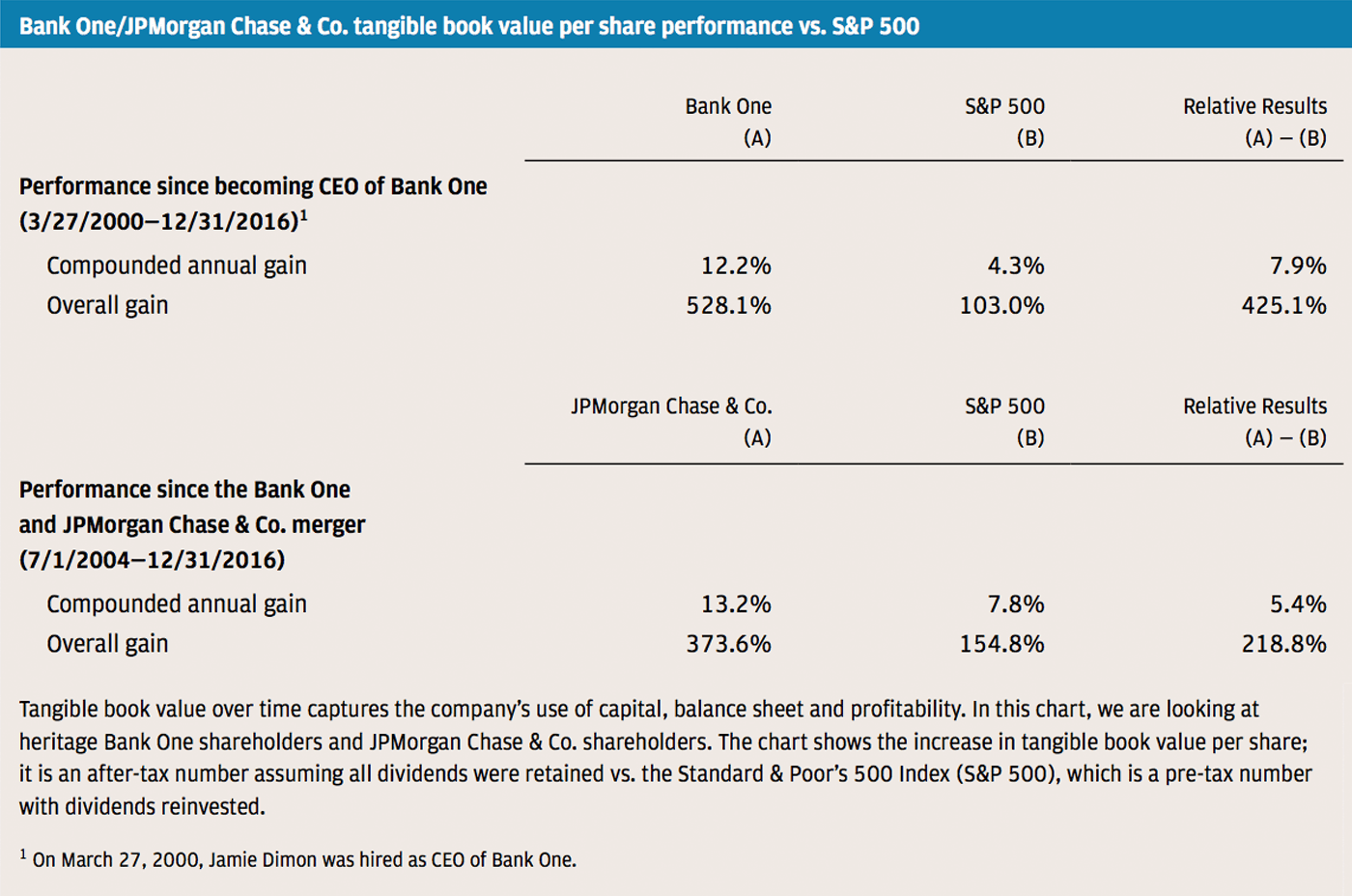

As you know, we believe tangible book value per share is a good measure of the value we have created for our shareholders. If we believe our asset and liability values are appropriate — and we do — and if we believe we can continue to deploy this capital at an approximate 15% return on tangible equity, which we do, then our company should ultimately be worth considerably more than tangible book value. If you look at the chart below, you’ll see that tangible book value “anchors” the stock price.

In the last five years, we have bought back $25.7 billion in stock. In prior years, I have explained why buying back our stock at tangible book value per share was a no-brainer. While the first and most important use of capital is to invest in growth, buying back stock should also be considered when you are generating excess capital. We do currently have excess capital. Five years ago, we offered the example of our buying back stock at tangible book value and having earnings per share and tangible book value per share substantially higher than they otherwise would have been just four years later. While we prefer buying our stock at tangible book value, we think it makes sense to do so at or around two times tangible book value for reasons similar to those we’ve expressed in the past. If we buy back a big block of stock this year (using analyst earnings estimates for the next five years), we would expect earnings per share in five years to be 3%–4% higher, and tangible book value would be virtually unchanged.

In this letter, I discuss the issues highlighted — which describe many of our successes and opportunities, as well as our challenges and responses. Like last year’s letter, we have organized much of the content around some of the key questions we have received from shareholders and other interested parties.

I. The JPMorgan Chase franchise

- Why do we consider our four major business franchises strong and market leading?

- Why are we optimistic about our future growth opportunities?

- What are some technology and fintech initiatives that you’re most excited about?

- How do we protect customers and their sensitive information while enabling them to share data?

- What are your biggest geopolitical risks?

- Although banks and other large companies remain unpopular with some people, you often say how proud you are of JPMorgan Chase. Why?

II. Regulatory reform

- Talk about the strength and safety of the financial system and whether Too Big to Fail has been solved.

- How and why should capital rules be changed?

- How do certain regulatory policies impact money markets?

- How has regulation affected monetary policy, the flow of bank credit and the growth of the economy?

- How can we reform the mortgage markets to give qualified borrowers access to the credit they need?

- How can we reduce complexity and create a more coherent regulatory system?

- How can we harmonize regulations across the globe?

III. Public policy

- The United States of America is truly an exceptional country.

- But it is clear that something is wrong — and it’s holding us back.

- How can we start investing in our people to help them be more productive and share in the opportunities and rewards of our economy?

- What should our country be doing to invest in its infrastructure? How does the lack of a plan and investment hurt our economy?

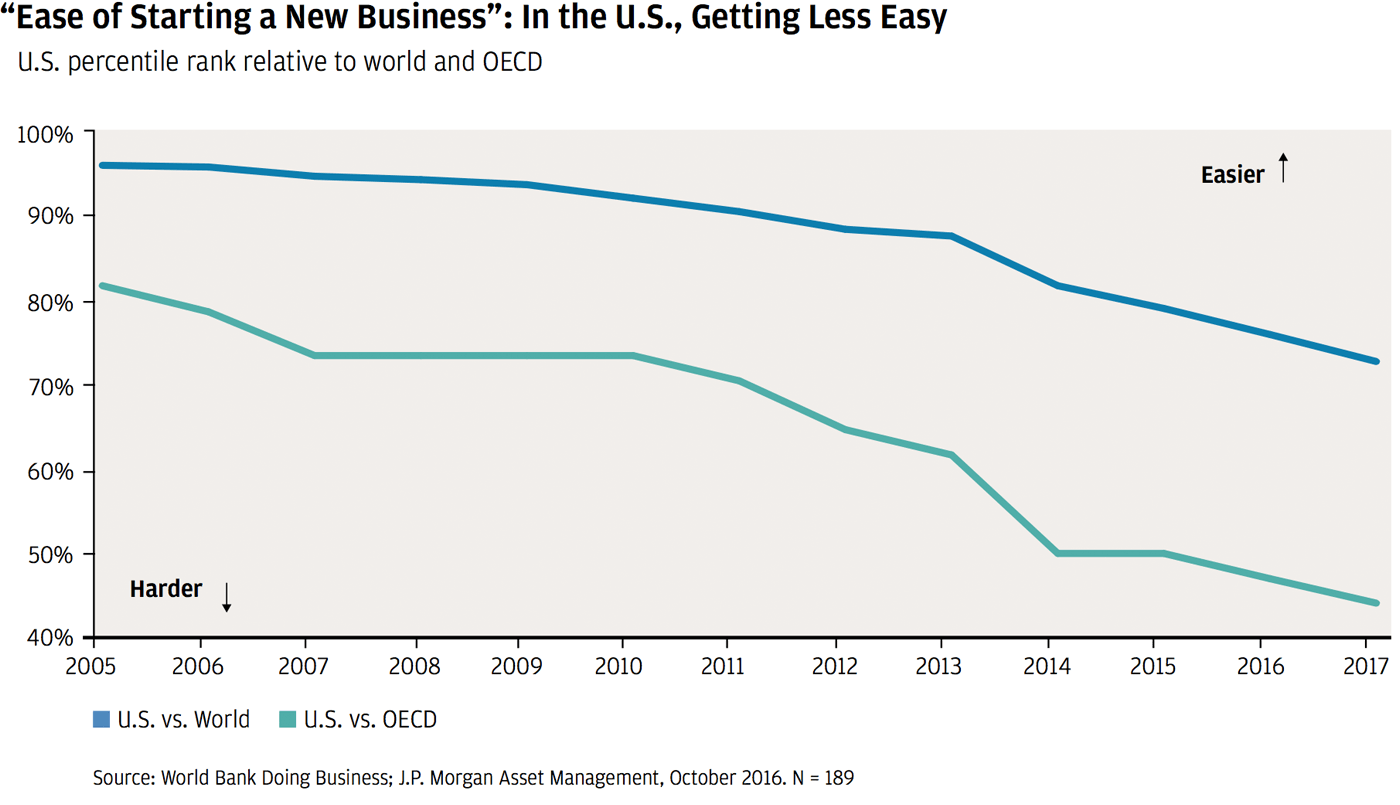

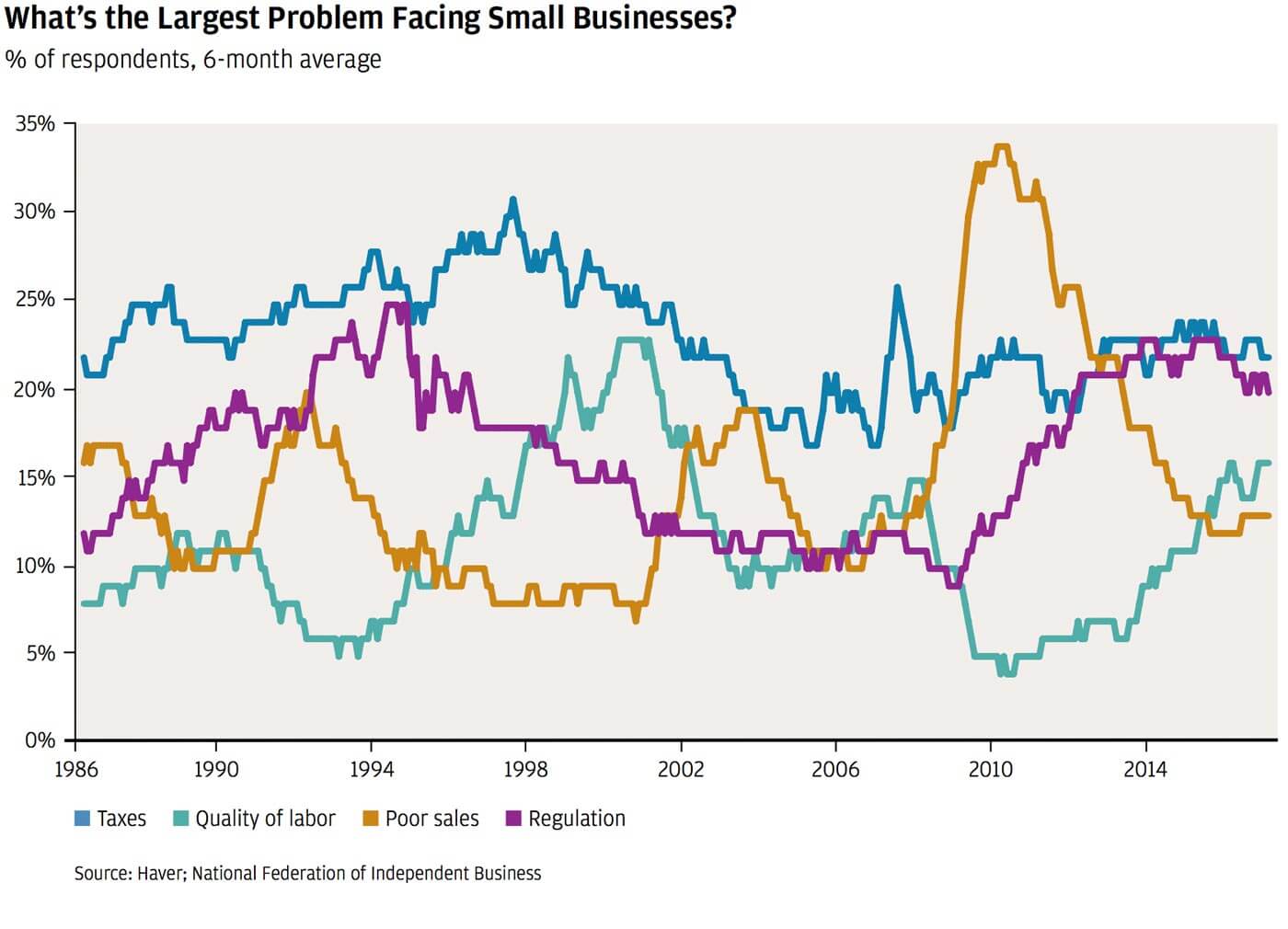

- How should the U.S. legal and regulatory systems be reformed to incentivize investment and job creation?

- What price are we paying for the lack of understanding about business and free enterprise?

- Strong collaboration is needed between business and government.

I. THE JPMORGAN CHASE FRANCHISE

1. Why do we consider our four major business franchises strong and market leading?

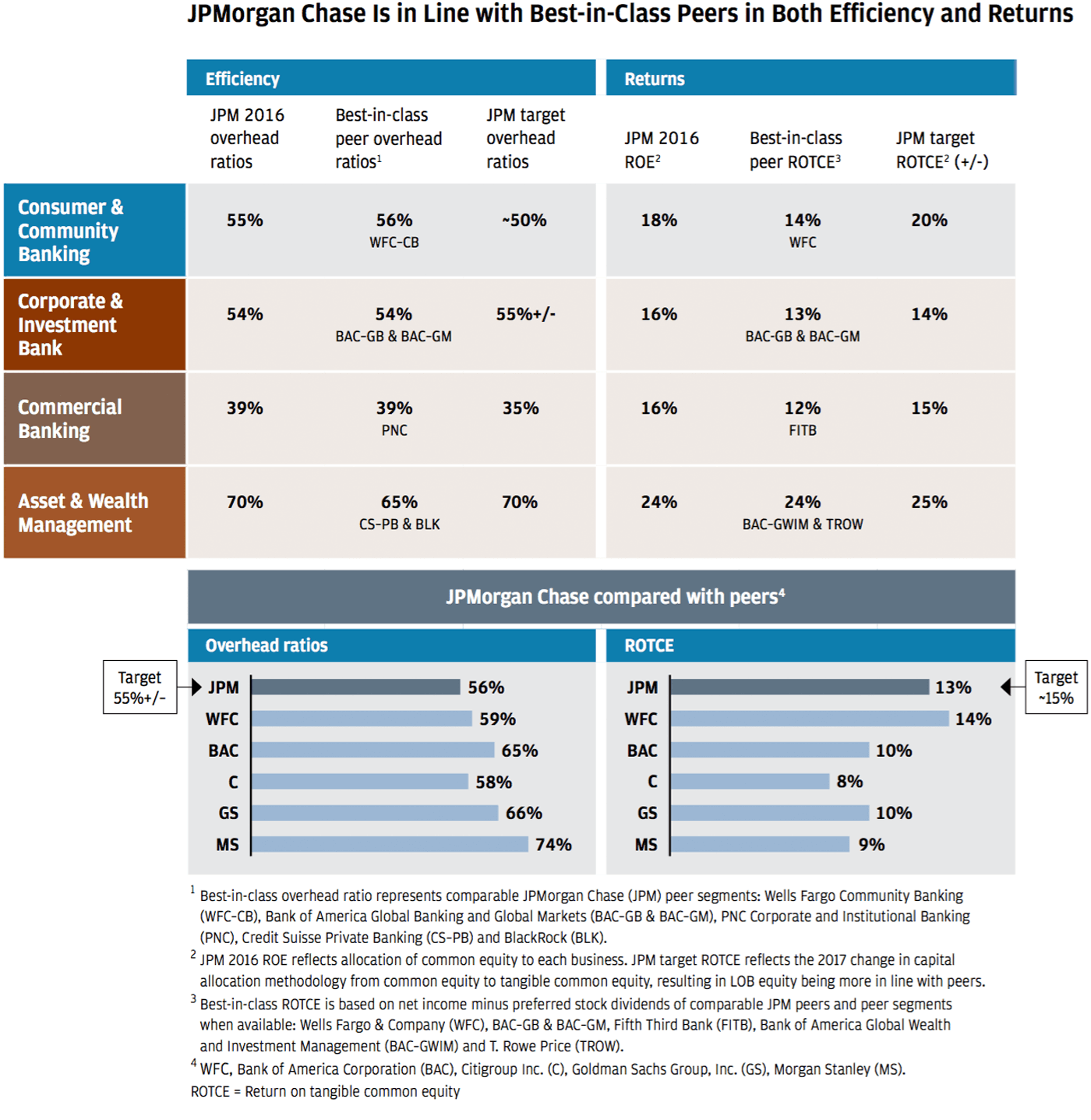

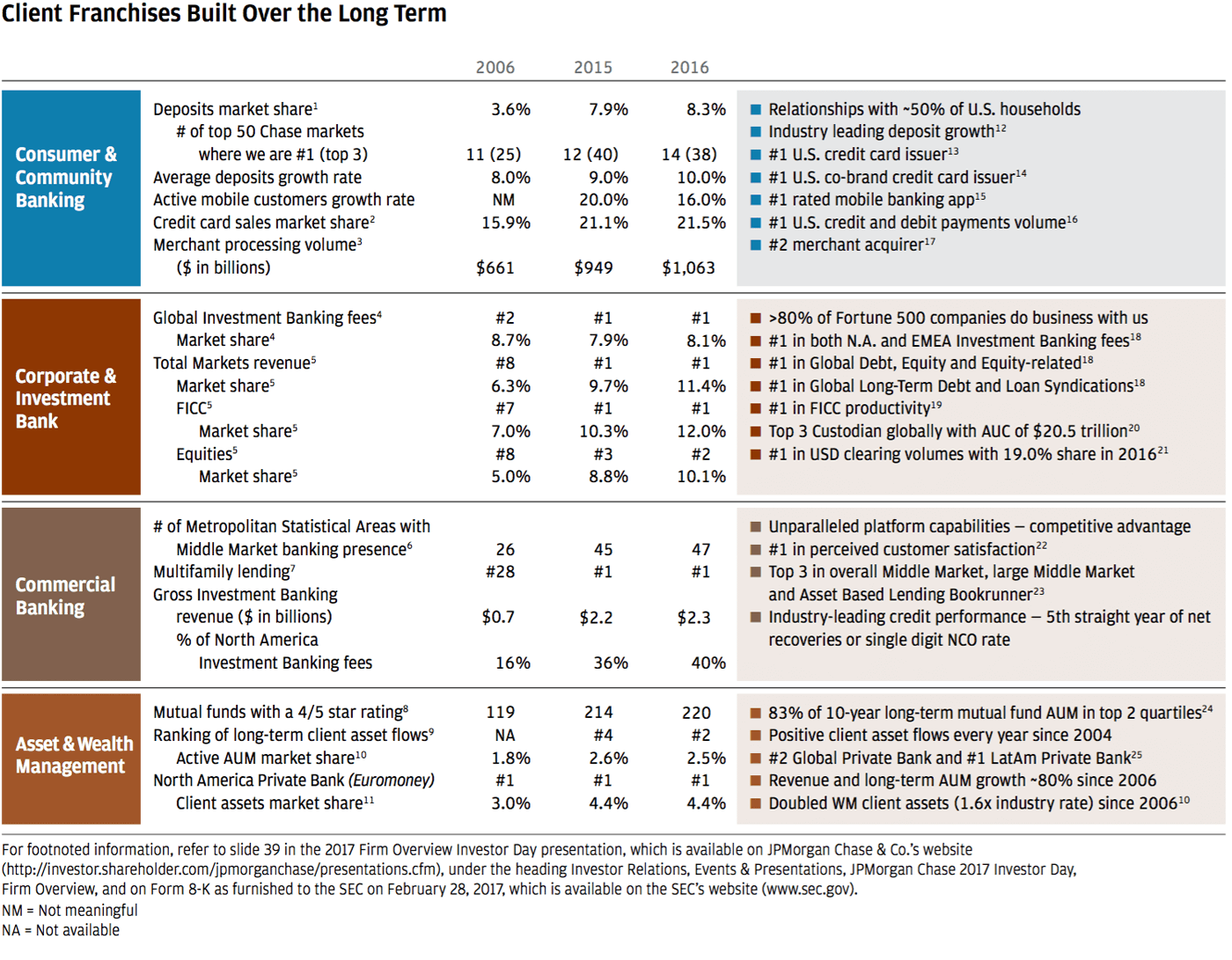

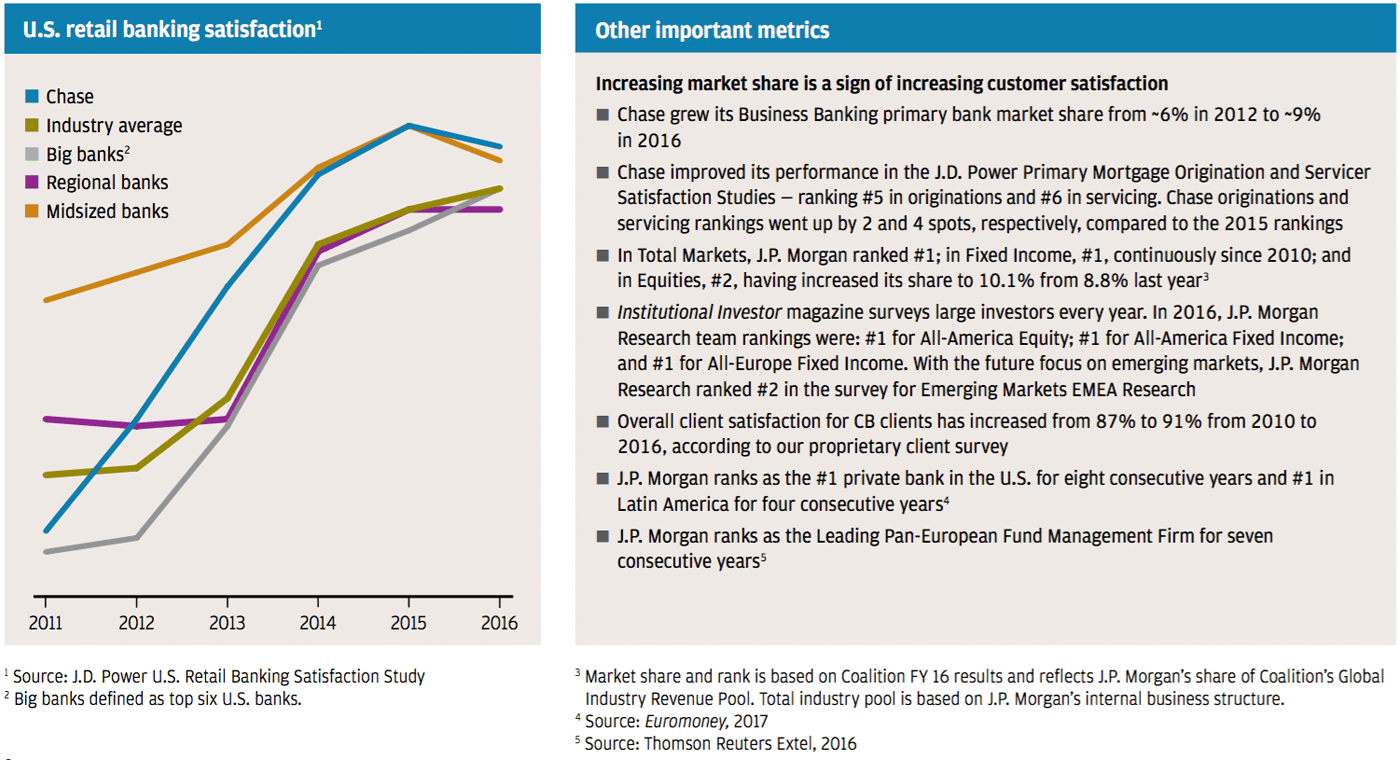

The charts below speak for themselves. Looking closely at the actual numbers, it’s clear that every business is among the top performers financially – whether you look at efficiency (overhead ratios) or return on equity (ROE) vs. the best in that business. More important, customer satisfaction is at the center of everything we do. Each business has gained market share – which is possible only when you are improving customer satisfaction and your products and services relative to the competition. And each business continues to innovate, from customer-facing apps, to straight through processing, to digitized trading services or payment systems. Our business leaders do a great job describing their businesses, and I strongly encourage you to read their letters following this year’s Letter to Shareholders. Each will give you a feel for why we are optimistic about our future.

Increasing Customer Satisfaction

2. Why are we optimistic about our future growth opportunities?

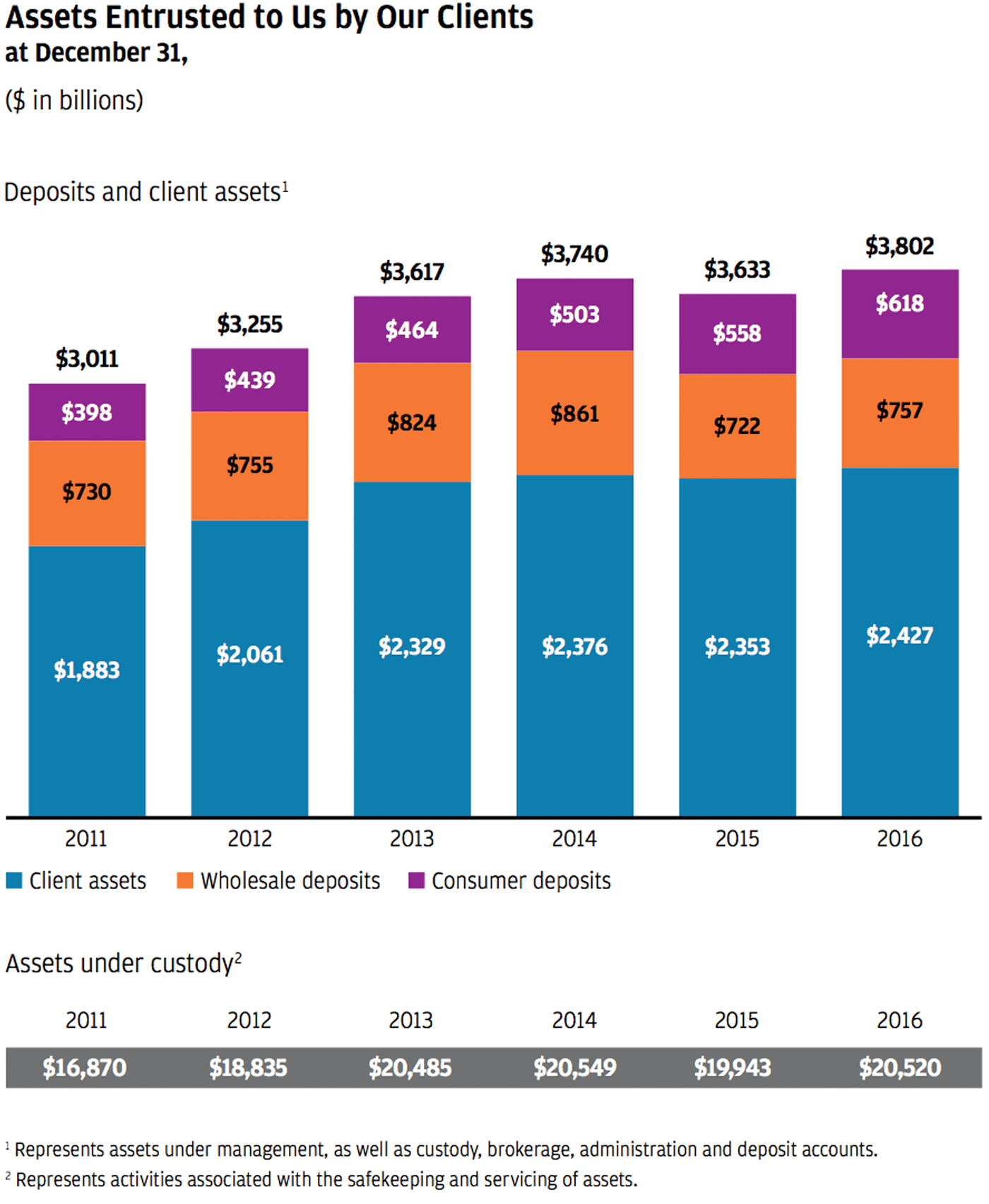

We believe we have substantial opportunities in the decades ahead to drive organic growth in our company. We have confidence in the underlying growth in the U.S. and global economies, which will fuel the growth in our customer base – consumer deposits, assets under management and small to large clients globally. This growth will obviously be faster in emerging markets than in developed markets – and we are well-positioned to serve both. In addition, we believe we can continue to gain share in many markets and, over time, add new, relevant products. This can drive organic growth for years. Capturing this growth is very basic:

- Selectively adding investment bankers and private bankers around the world

- Bringing consumer and commercial banking branches and capabilities to more places in the United States

- Adding wholesale branches overseas and carefully expanding into new countries

- Adding wholesale and Private Bank clients as they grow into our target space

Equally important is using technology and fintech to do a better job serving clients and to grow our businesses – with better products and services. You can read more about our big data, machine learning, payment systems, cybersecurity and electronic trading as described by our senior executives in the Line of Business CEO letters to shareholders. But I do want to highlight a few items in the next question that pertain to these topics.

3. What are some technology and fintech initiatives that you’re most excited about?

One of the reasons we’re performing well as a company is we never stopped investing in technology – this should never change. In 2016, we spent more than $9.5 billion in technology firmwide, of which approximately $3 billion is dedicated toward new initiatives. Of that amount, approximately $600 million is spent on emerging fintech solutions – which include building and improving digital and mobile services and partnering with fintech companies. The reasons we invest so much in technology (whether it’s digital, big data or machine learning) are simple: to benefit customers with better, faster and often cheaper products and services, to reduce errors and to make the firm more efficient.

We are developing great new products.

We are currently developing some exciting new products and services, which we will be adding to our suite and rolling out later this year, including:

- End-to-end digital banking – The ability to open an account and complete the majority of transactions on a mobile phone.

- Investment advice and self-directed investing – Online vehicles for both individual retirement and non-retirement accounts, providing easy-to-use (and inexpensive) automated advice, as well as enabling our customers to buy and sell stocks and bonds, etc. (again inexpensively).

- Electronic trading and other online services (e.g., cash management) in our Corporate & Investment Bank and Asset & Wealth Management businesses – Offering our clients a more robust digital platform.

We are investing in data and technology to improve the financial health of low-income households.

Over the last two years, the JPMorgan Chase Institute has helped identify some of the most pressing financial challenges facing American households, such as their difficulty managing income and expense volatility. We are using that data to select and support innovative fintech companies and nonprofits that are designing solutions to address these challenges. One example of these efforts is JPMorgan Chase’s Financial Solutions Lab, which, in partnership with the Center for Financial Services Innovation, seeks to facilitate the next generation of fintech products to help consumers manage their daily finances and meet their long-term goals. Highlights of the initiative include:

- To date, the Lab has helped support more than 18 fintech companies working to improve the financial health of more than 1 million Americans. One example is Digit, an automated savings tool that identifies small amounts of money that can be moved into savings based on spending and income. To date, it has helped Americans save more than $350 million.

- Lab winners have raised more than $100 million in follow-on capital.

- In 2017, we launched a new competition seeking innovative fintech solutions to promote the financial health of populations often overlooked, such as people of color, individuals with disabilities and low-income women.

We are successfully collaborating with other companies to deliver fintech solutions.

Whether it is consumer payment systems (Zelle), mortgages (Roostify), auto finance (TrueCar), small business lending (OnDeck Capital) or communications systems (Symphony), we are successfully collaborating with some excellent fintech companies to dramatically improve our digital and other customer offerings. I’d like to highlight just two new exciting areas:

- Developer Services API store – By providing direct interfaces with our applications (fully controlled, of course), we are enabling entrepreneurs, partners, fintech companies and clients to build new products or services dedicated to specific needs.

- Bill payment and business services – While I can’t reveal much at the moment, suffice it to say there are some interesting developments coming as we integrate our capabilities with those of other companies.

4. How do we protect customers and their sensitive information while enabling them to share data?

For years, we have been describing the risks – to banks and customers – that arise when customers freely give away their bank passcodes to third-party services, allowing virtually unlimited access to their data. Customers often do not know the liability this may create for them, if their passcode is misused, and, in many cases, they do not realize how their data are being used. For example, access to the data may continue for years after customers have stopped using the third-party services.

We recently completed a new arrangement with Intuit, which we think represents an important step forward. In addition to protecting the bank, the customers and even the third party (in this case, Intuit), it allows customers to share data – how and when they want. Under this arrangement, customers can choose whatever they would like to share and opting to turn these selections on or off as they see fit. The data will be “pushed” to Intuit, eliminating the need for sharing bank passcodes, which protects the bank and our customers and reduces potential liabilities on Intuit’s part as well. We are hoping this sets a new standard for data-sharing relationships.

5. What are your biggest geopolitical risks?

Banks have to manage a lot of risks – from credit and trading risks to technological, operational, conduct and cybersecurity risks. But in addition to those, we have exposures around the world, which are subject to normal cyclical and recession risks, as well as to complex geopolitical risks.

There are always geopolitical risks, and you can rest assured we are continuously reviewing, analyzing and stress testing them to ensure that our company can endure them. We always try to make certain that we can handle the worst of all cases – importantly, without disrupting the effective operation of the company and its service to our clients. We think these geopolitical risks currently are in a heightened state – that is, beyond what we might consider normal. There are two specific risks I want to point out:

Brexit and the increasing risk to the European Union (EU).

Regarding Brexit, a key concern is to make sure our company is prepared to support our clients on day one – the first day after the actual Brexit occurs, approximately two years from now. We are confident we will be able to develop and expand the capabilities that our EU subsidiaries and branches will need to serve our clients properly in Europe under EU law. This will require acquiring regulatory approvals, transferring certain technologies and moving some people. On day one, we need to perform all of our critical functions at our standards. For example, underwriting debt and equity, moving money and accepting deposits, and safeguarding the custody assets for all of our European clients, including many sovereigns themselves. We must be prepared to do this assuming a hard exit by the United Kingdom – it would be irresponsible to presume otherwise. While this does not entail moving many people in the next two years, we do suspect that following Brexit, there will be constant pressure by the EU not to “outsource” services to the United Kingdom but to continue to move people and capabilities into EU subsidiaries.

We hope that the advent of Brexit would lead the EU to focus on fixing its issues – immigration, bureaucracy, the ongoing loss of sovereign rights and labor inflexibility – and thereby pulling the EU and the monetary union closer together. Our fear, however, is that it could instead result in political unrest that would force the EU to split apart. The unraveling of the EU and the monetary union could have devastating economic and political effects. While we are not predicting this will happen, the probabilities have certainly gone up – and we will keep a close eye on the situation in Europe over the next several years.

De-globalization, Mexico and China.

Anti-globalization sentiment is growing in parts of the world today, usually expressing itself in anti-trade and anti-immigration positions. (I’m not going to write about immigration in this letter – we have always supported proper immigration – it is a vital part of the strength of America, and, properly done, it enhances the economy and the vitality of the country.) We do not believe globalization will reverse course – we believe trade has been absolutely critical for growth around the world and has benefited billions of people. While there are some issues with our trade policies that need to be fixed, poorly conceived anti-trade policies could be quite disruptive, particularly with two of our key trading partners: Mexico and China.

The trade deal with Mexico through NAFTA is simpler than the one with China. (In full disclosure, JPMorgan Chase is a major international bank in Mexico, with revenue of more than $400 million, serving Mexican, American and international clients who do business there.) Mexico is a long-standing peaceful neighbor, and it is wholly in our country’s interest that Mexico be a prosperous nation. This actually reduces immigration issues (there are now more Mexicans going back to Mexico than coming into the United States). Our trade agreement with Mexico helps ensure that the young democracy in Mexico is not hijacked by populist and anti-American leaders (like Chavez did in Venezuela). While there are some clear, identifiable problems with NAFTA, I believe they will be worked out in a way that is fair and beneficial for both sides. The logic to do so is completely compelling.

China is far more complex. (Again, in full disclosure, we have a major international presence in China, with revenue of approximately $700 million, serving Chinese, American and international clients who do business in that country.) The United States has some serious trade issues with China, which have grown over the years – from cybersecurity and the protection of intellectual property to tariffs, non-tariff trade barriers and non-fulfillment of World Trade Organization obligations. However, there is no inevitable or compelling reason that China and America have to clash – in fact, improving political and economic relationships can be good for both parties. So while the issues here are not easy, I am hopeful they can be resolved in a way that is fair and constructive for the two countries.

6. Although banks and other large companies remain unpopular with some people, you often say how proud you are of JPMorgan Chase. Why?

I firmly believe the qualities embedded in JPMorgan Chase today – the knowledge and cohesiveness of our people, our deep client relationships, our technology, our strategic thinking and our global presence – cannot be replicated. While we take nothing for granted, as long as we continue to do our jobs well and continue to drive our company forward, we think we can be a leader for our industry and the communities we serve for decades to come. There are times when I am bursting with pride with what we have accomplished for our clients, communities and countries around the world – let me count (some of) the ways:

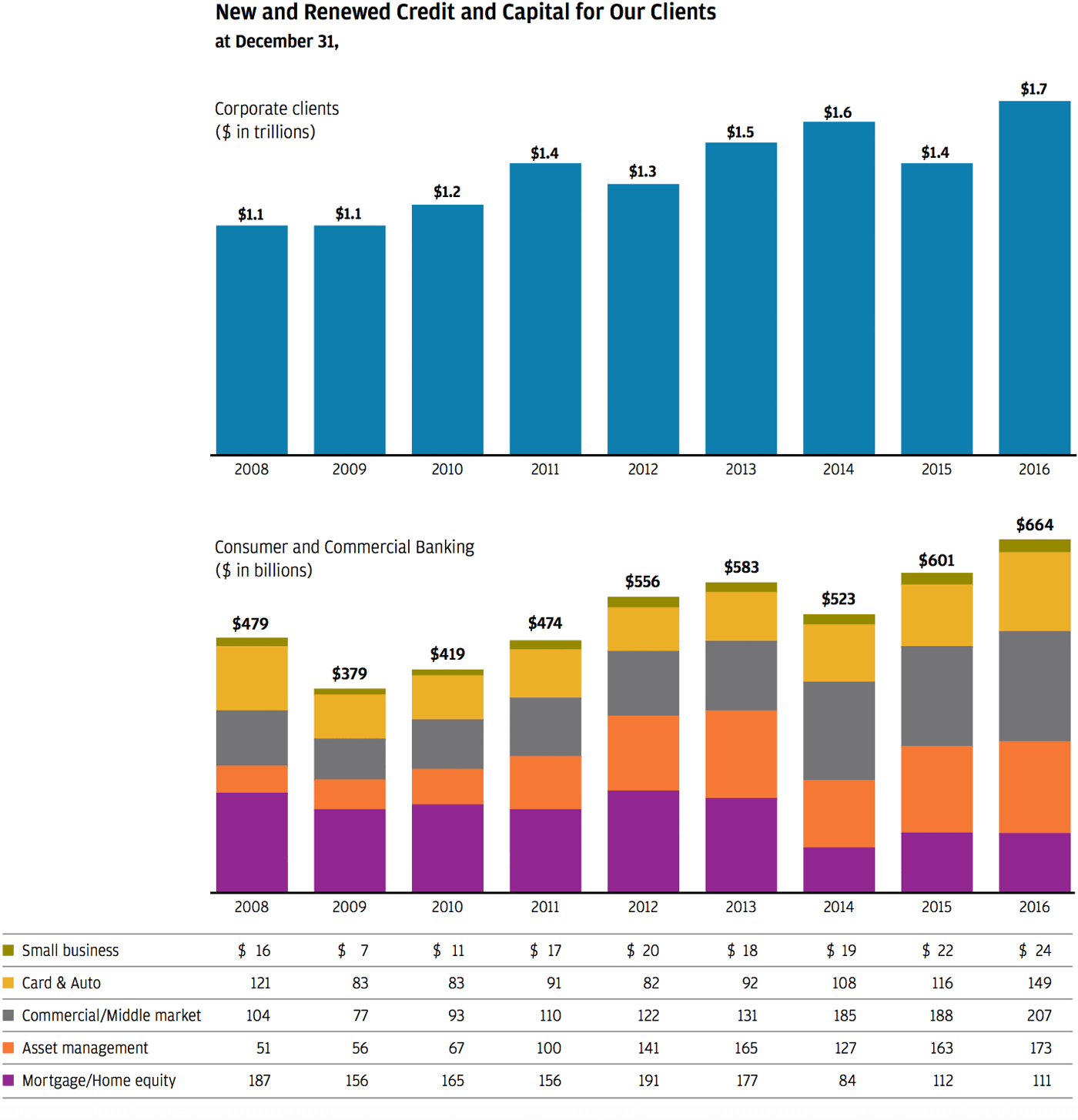

We are strong and steadfast and are there for our clients in good times and bad.

In the toughest of times, we maintained a healthy and vibrant company that was able to do its job – we did not need government support and, in fact, we consistently provided credit and capital to our clients and assistance to our government throughout the crisis. I want to remind our shareholders that we continued to lend not at the much higher prevailing market rates at that time but at existing bank rates. These were far below market rates because our clients relied on us – we were their lender of last resort. JPMorgan Chase was and will be a Rock of Gibraltar in the best and worst of times for our clients around the world.

We have extraordinary capabilities — both our people and our technology.

Ultimately, our people are our most important assets – and they are exceptional. Their knowledge, their capabilities and their relationships are what drive everything else, including our technology and our innovation. They partner well with each other around the world, and they are deeply trusted by our clients and within our communities. We all owe them an enormous debt. They are the ones accomplishing all the things you are reading about in this Annual Report.

Our fortress balance sheet and the strength of our people were never more vividly evident than during the darkest hours of the financial crisis. I was in awe of the tremendous effort our people made (thousands of people, seven days a week for months) to acquire and assimilate Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual – thereby saving 30,000 jobs and avoiding the devastation of communities that would have happened if those companies had been allowed to fail. Our company went above and beyond the call of duty during the height of the crisis, including lending $87 billion to a bankrupt Lehman to facilitate, as much as possible, an orderly unwind of its assets. In those dark days, we were the only bank willing to commit to lending $4 billion to the state of California, $2 billion to the state of New Jersey and $1 billion to the state of Illinois to keep those states strong. None of these actions had to be taken, and they were made at some risk to JPMorgan Chase. We simply were acting to do our part to try to stop the crisis from getting worse.

We try to be outstanding corporate citizens.

We believe in being great corporate citizens – in how we treat our employees and care for our clients and communities. Let me give some examples to illustrate this point:

- We compensate our employees fairly and provide extraordinary benefits and

training. We value our employees at JPMorgan Chase, and we are

committed to helping them succeed. This past year, we

announced that we will increase our minimum wages –

mostly for entry-level bank tellers and customer service

representatives – to between $12.00 and $16.50 an hour

(depending on where these employees live). This will

increase wages for approximately 18,000 employees. We

believe this pay increase is the right thing to do, and,

above all, it enables more people to begin to share in

the rewards of our success. Remember, many of these

employees soon move on to even higher paying

jobs.

We will also continue to invest in employee benefits and training opportunities so that our workers can continue to increase their skills and advance their careers. Our comprehensive benefits package, including healthcare and retirement savings, on average, is valued at $11,000 per year. Our total investment in training and development is approximately $325 million a year. Together, these efforts help our employees support their families, advance their careers and promote economic growth in our communities. - We have a diverse workforce. We have more than 243,000 employees

globally with over 167,000 in the United

States. Women represent 50% of our

employees. Recently, Oliver Wyman, a

leading global management consulting

firm, issued a report stating that it

would be 30 years before women reach 30%

Executive Committee representation

within global financial services. So you

might be surprised to find out that

women already represent 30% of my direct

reports and approximately 30% of our

company’s senior leadership globally.

They run major businesses – several

units on their own would be among

Fortune 1000 companies. In addition to

having three women on our Operating

Committee – who run Asset & Wealth

Management, Finance and Legal – some of

our other businesses and functions

headed by women include Consumer

Banking, Credit Card, U.S. Private Bank,

U.S. Mergers & Acquisitions, Global

Equity Capital Markets, Global Research,

Regulatory Affairs, Global Philanthropy,

our U.S. branch network, our Controller

and firmwide Marketing. I believe we

have some of the best women leaders in

the corporate world globally. In

addition to gender diversity, 48% of our

firm’s population is ethnically diverse

in the United States, and we are in more

than 60 countries around the world.

Diversity means running a company where

people are respected, trusted and given

equal opportunity to contribute and

raise their ideas and

voices.

But there is one area in particular where we simply have not met the standards JPMorgan Chase has set for itself – and that is in increasing African-American talent at the firm. While we think our effort to attract and retain black talent is as good as at most other companies, it simply is not good enough. Therefore, in 2016, we introduced a new firmwide initiative called Advancing Black Leaders. This initiative is dedicated to helping us better attract and recruit external black talent while retaining and developing the talent within the company. And we are proud of our efforts this past year – we increased the number of black employees at the officer level (through both internal promotions and external new hires), we focused on the pipeline of junior talent, and we increased the number at the senior officer and vice president level. We plan to continue to make progress on this front in the years to come. - We are proud of how we are helping veterans. We want to continue to update you on how JPMorgan Chase has helped position military members, veterans and their families. Our program is centered on facilitating success in their post-service lives primarily through employment and retention. In 2011, JPMorgan Chase and 10 other companies launched the 100,000 Jobs Mission, setting a goal of collectively hiring 100,000 veterans. The initiative now includes more than 200 companies, has collectively hired nearly 400,000 veterans, and is focused on collectively hiring 1 million people. JPMorgan Chase alone has hired more than 11,000 veterans since 2011. We hope you feel as good about this initiative as we do.

- We have accomplished an extraordinary amount in our Corporate Responsibility

efforts. We take this responsibility very seriously, and, over the

last decade, not only have we more than doubled our

philanthropic giving from approximately $100 million to

approximately $250 million in 2016, but we have dramatically

increased our support with human capital, collaboration,

data and management expertise. Our head of Corporate

Responsibility talks about our significant measures in more

detail in his letter, but I will highlight two initiatives

below:

- We provide tremendous support to cities and communities – especially those

left behind – and the best example is our work in Detroit. JPMorgan Chase

has been doing business in Detroit for more than 80 years, and we watched as

this iconic American city was engulfed in economic turmoil after years of

decline. Just as Detroit was declaring bankruptcy, our company redoubled its

efforts to help and, in 2014, announced our most comprehensive initiative to

date – a $100 million investment in Detroit to help accelerate the city’s

recovery.

We are making strategic, coordinated investments focused on creating economically inclusive and revitalized neighborhoods, preparing people with the skills needed for today’s high-quality jobs and providing small businesses with the capital they need to grow and succeed. This includes our investment in the Strategic Neighborhoods Fund, which brings together community developers and dedicated resources to create and maintain affordable housing and deliver services to targeted communities. We also seeded the city’s first nonprofit real estate development firm focused exclusively on creating and preserving affordable housing in Detroit’s neighborhoods. In 2015, we helped create the $6.5 million Entrepreneurs of Color Fund with the Kellogg Foundation and Detroit Development Fund to bring critical financing and technical assistance to underserved minority- and community-based small businesses. In its first year, the Fund deployed almost $3 million in capital through more than 30 loans. We are also putting our talented employees to work in Detroit through the Detroit Service Corps. Since 2014, 68 JPMorgan Chase employees from 10 countries dedicated three intensive weeks to 16 Detroit nonprofits, helping them analyze challenges, solve problems and improve their chances for success. Detroit is making incredible progress as a result of the unprecedented spirit of engagement and cooperation among the city’s leaders, business community and nonprofit sectors. JPMorgan Chase is proud to be part of Detroit’s resurgence, and we believe a thriving Detroit economy will become a shining example of American resilience and ingenuity at work. - And more broadly, we created solutions for one of our country’s biggest challenges – training the world’s workforce in the skills needed to compete in today’s economy. Through several targeted initiatives, JPMorgan Chase is investing over $325 million in demand-driven workforce development initiatives around the world. Our programs build stronger labor markets that create economic opportunity, focusing on middle-skill jobs – positions that require a high school education, and often specialized training or certifications, but not a college degree. These jobs – surgical technologists, diesel mechanics, help desk technicians and more – offer good wages and the chance to move up the economic ladder. Our goal is to increase the number of workers who have access to career pathways, whether they are adults looking to develop new skills or younger workers starting to prepare for careers during high school and ending with postsecondary degrees or credentials aligned with good-paying, high-demand jobs. We are very proud that we can be a bridge between businesses and job seekers to support an economy that creates opportunity for everyone.

- We provide tremendous support to cities and communities – especially those

left behind – and the best example is our work in Detroit. JPMorgan Chase

has been doing business in Detroit for more than 80 years, and we watched as

this iconic American city was engulfed in economic turmoil after years of

decline. Just as Detroit was declaring bankruptcy, our company redoubled its

efforts to help and, in 2014, announced our most comprehensive initiative to

date – a $100 million investment in Detroit to help accelerate the city’s

recovery.

II. Regulatory Reform

We had a severe financial crisis followed by needed reform, and our financial system is now stronger and more resilient as a result. During and since the crisis, we’ve always supported thoughtful, effective regulation, not simply more or less. But it is an understatement to say improvements could be made. The regulatory environment is unnecessarily complex, costly and sometimes confusing. No rational person could think that everything that was done was good, fair, sensible and effective, or coherent and consistent in creating a safer and stronger system. We believe (and many studies show) that poorly conceived and uncoordinated regulations have damaged our economy, inhibiting growth and jobs – and this has hurt the average American. We are not looking to throw out the entirety of Dodd-Frank or other rules (many of which were not specifically prescribed in Dodd-Frank). It is, however, appropriate to open up the rulebook in the light of day and rework the rules and regulations that don’t work well or are unnecessary. Rest assured, we will be responsibly and reasonably engaged on this front. We believe changes can and should be made that preserve the safety and soundness of the financial system and lead to a more healthy and vibrant economy for the benefit of all.

There are some basic principles that should guide responsible regulation:

- Coherence of rules to be coordinated both within and across regulatory agencies

- Global harmonization of regulation to enhance fair trade and competition while helping eliminate any weak links in the global system

- Simplified and proper risk-based capital standards

- Consistent and transparent capital and liquidity rules

- Regular and rigorous regulatory review, including consideration of costs vs. benefits, efficiencies, competitiveness, reduction of redundant costs and assessment of impact on economic growth

Adhering to these principles will maximize safety and soundness, increase competition and improve economic health.

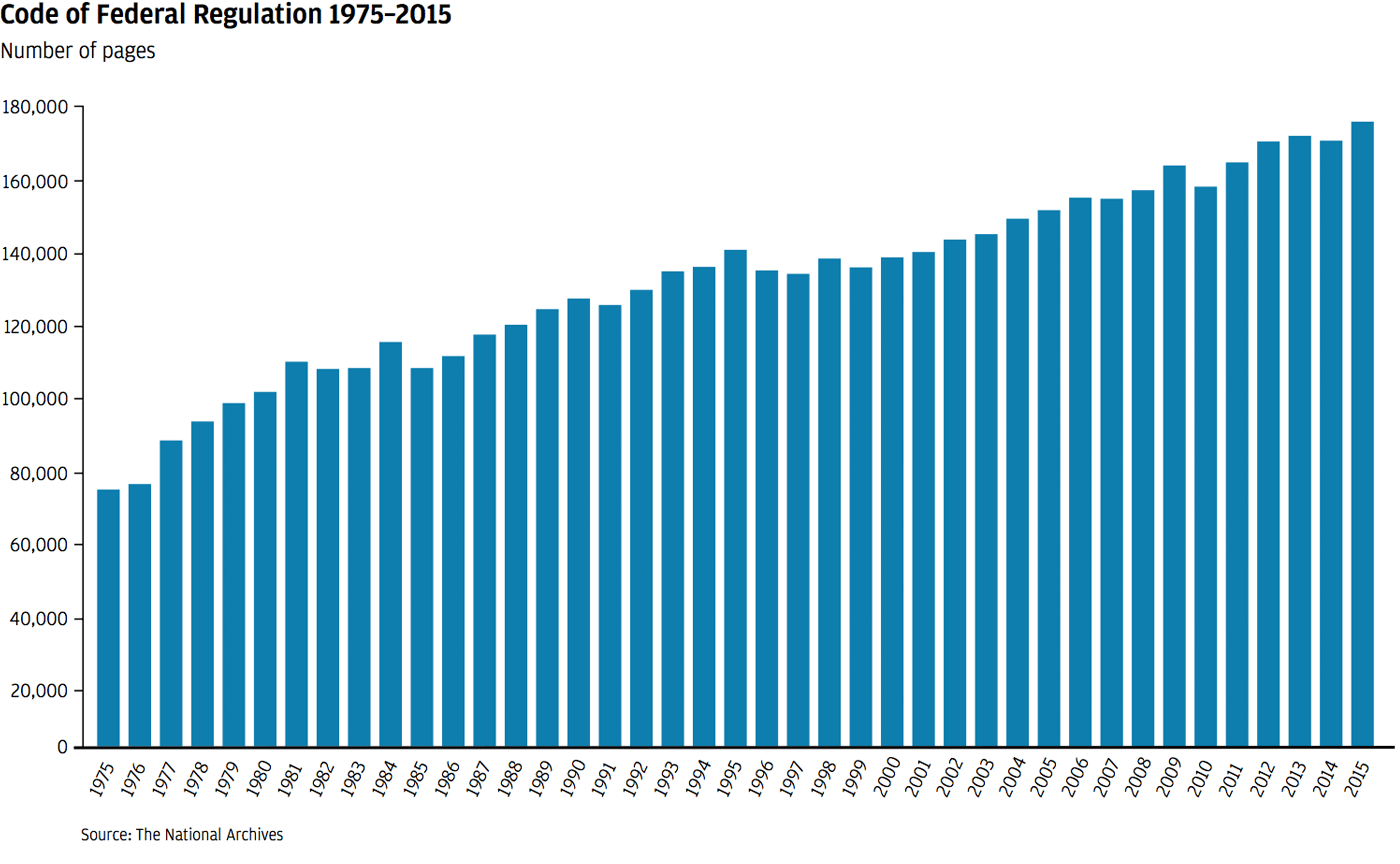

Since the financial crisis, thousands of new rules and regulations have been put into place by multiple regulators in the United States and around the world. An already complex system of financial oversight and supervision has grown even more complex – and this complexity can sometimes create even more risk. Many of these rules and regulations should be examined and possibly modified, but I will focus on the few that are critical in response to some of the questions and topics that follow.

1. Talk about the strength and safety of the financial system and whether Too Big to Fail has been solved.

There is no question that the system is safer and stronger today, and this is mostly due to the following factors:

- Dramatically higher capital for almost all banks (we’ll talk later about how much capital is the appropriate amount)

- Far higher liquidity for almost all banks (again, we’ll provide more details later in this section)

- More disclosure and transparency – both to investors and regulators

- More coordinated oversight within the United States and abroad

- Far stronger compliance and control systems

- Laws that allow regulators to step in to unwind not only failing banks but investment banks (this did not exist for investment banks prior to the financial crisis)

- The creation of “bail-in-able” unsecured debt – this converts debt into equity at the time of failure, immediately recapitalizing the failed bank

- New rules that prohibit derivatives contracts from being voided at bankruptcy – this allows derivatives contracts to stay in place, creating an orderly transition to bankruptcy

- Stress testing that monitors banks’ balance sheets and capital ratios under severely adverse scenarios (more on this below)

- Requirements for banks and investment banks to prepare corporate recovery plans in the event of a crisis to prevent bankruptcy (these plans did not exist before the financial crisis)

These changes taken together not only largely eliminate the chance of a major bank failing today but also prevent such failure from having a threatening domino effect on other banks and the economy as a whole. And if a major bank does fail, regulators have the necessary tools to manage it in an orderly way. Moreover, the banking industry itself has an inherent interest in the safety and soundness of the financial system because if there is a failure, the entire industry will be liable for that cost (more on that below).

Essentially, Too Big to Fail has been solved — taxpayers will not pay if a bank fails.

The American public has the right to demand that if a major bank fails, they, as taxpayers, would not have to pay for it, and the failure wouldn’t unduly harm the U.S. economy. In my view, these demands have now both been met.

On the first count, if a bank fails, taxpayers do not pay. Shareholders and debtholders, now due to total loss absorbing capacity (TLAC) rules, are at risk for all losses. To add belts and suspenders, if all that capital is not enough, the next and final line of defense is the industry itself, which is legally liable to pay any excess losses. (Notably, since 2007, JPMorgan Chase alone has contributed $11.7 billion to the industry deposit fund.)

On the second count, a regulatory takeover of a major bank would be orderly because regulators have the tools to manage it in the right way.

It is instructive to look at what would happen if Lehman were to fail in today’s regulatory regime. First of all, it is highly unlikely the firm would fail because the new requirements would mean that instead of Lehman’s equity capital being $23 billion, which it was in 2007, it would be approximately $45 billion under today’s capital rules. In addition, Lehman would have far stronger liquidity and “bail-in-able” debt. And finally, the firm would be forced to raise capital much earlier in the process.

If Lehman failed anyway, regulators would now have the legal authority to put the firm in receivership (they did not have that ability back in 2007–2008). The moment that happened, unsecured debt of approximately $120 billion would be immediately converted to equity. Derivatives contracts would not be triggered, and cash would continue to move through the pipes of the financial system. In other words, due to the living wills, Too Big to Fail was solved before any additional rules were put in place. (I’m not going to go into detail on the living wills but will say that while they have some positive elements, they have become unnecessarily complex and costly, and they need to be simplified.)

Last, there is a new push for Chapter 14 bankruptcy for banks, which we at JPMorgan Chase support.

This would provide specialized rules to quickly handle bankruptcy for banks. Whether a failed bank goes through Chapter 14, called “bankruptcy,” or Title II, called “resolution” – these are essentially the same thing – we should make the following point perfectly clear to the American people: A failed bank means the bank’s board and management are discharged, its equity is worthless, compensation is clawed back to the extent of the law and the bank’s name will forever be buried in the Hall of Shame. In addition, we should change the term “resolution” – as it sounds as if we are bailing out a failing bank (which couldn’t be further from the truth). Whatever the term is called, it should be made clear that the process is the same as bankruptcy in any other industry. One lesson from the prior crisis is that the American public will not be satisfied without “Old Testament Justice.”

But market panic will never disappear entirely, and regulations must be flexible enough to allow banks to act as a bulwark against it rather than forcing financial institutions into a defensive crouch that will only make things worse.

There will be market panic again, and it won’t affect just banks – it will affect the entire financial marketplace. Remember, banks were consistent providers of credit at existing prices into the crisis – the market was not. During the crisis, many companies could not raise money in the public markets, many securities did not trade, securities issuances dropped dramatically and many asset prices fell to valuation levels that virtually anticipated a Great Depression. Last time around, banks – in particular (and I say with pride) our bank – stood by their customers to provide capital and liquidity that helped them survive. However, today’s capital and liquidity rules have created rigidity that will actually hurt banks’ ability to stand against the tide as they did during the Great Recession. This will mean that banks will survive the next market panic with plenty of cushion that could have been – but may not have been – used to help customers, companies and communities.

It is in this environment that regulators need certain authorities to stop the situation from getting worse. One important point: Under both Chapter 14 and Title II, there might be a short-term need for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation or the Fed to lend money, in the short run with proper collateral, to a failing or failed institution. This is because panic can cause a run on the bank, and it is far less painful to the economy if that bank’s assets are not sold in fire sales. This lending is effectively fully secured, and no loss should ever be incurred. Again, any loss that did occur would be charged back to all the banks. This also gives banks an enormous incentive to be in favor of a properly designed, safe and sound system.

Going back to the principles above, putting safety and soundness first is clearly correct, but regulators also need the ability to take into consideration the costs and impact on our economy in various scenarios.

2. How and why should capital rules be changed?

We need consistent, transparent, simplified and more risk-based capital standards.

A healthy banking system needs consistent and transparent capital and liquidity rules that are based on simplified and proper risk-based standards. This allows banks to use capital intelligently and to properly plan capital levels over the years. Any rules that are capricious or that cause an arbitrary reduction in the value of a bank’s capital – and the value of the bank overall – can cause improper or inefficient risk taking. Finally, proper capital rules will allow a bank to do its job: to consistently finance the economy, in good times and, importantly, in bad times.

There are more than 20 different major capital and liquidity requirements – and they often are inconsistent. For example, certain liquidity rules force a bank to hold an increasing amount of cash, essentially deposited at the Fed, but other rules require the bank to hold capital against this risk-free cash. An extraordinary number of calculations need to be made as companies try to manage to avoid inadvertently violating one of the standards – a violation that rarely affects safety and soundness. To protect themselves, banks build enormous buffers – and buffers on top of buffers – or otherwise take unnecessary actions to ensure that they don’t step over the line. And finally, if we enter another Great Recession, the need for these buffers increases, which inevitably will force a bank to reduce its lending.

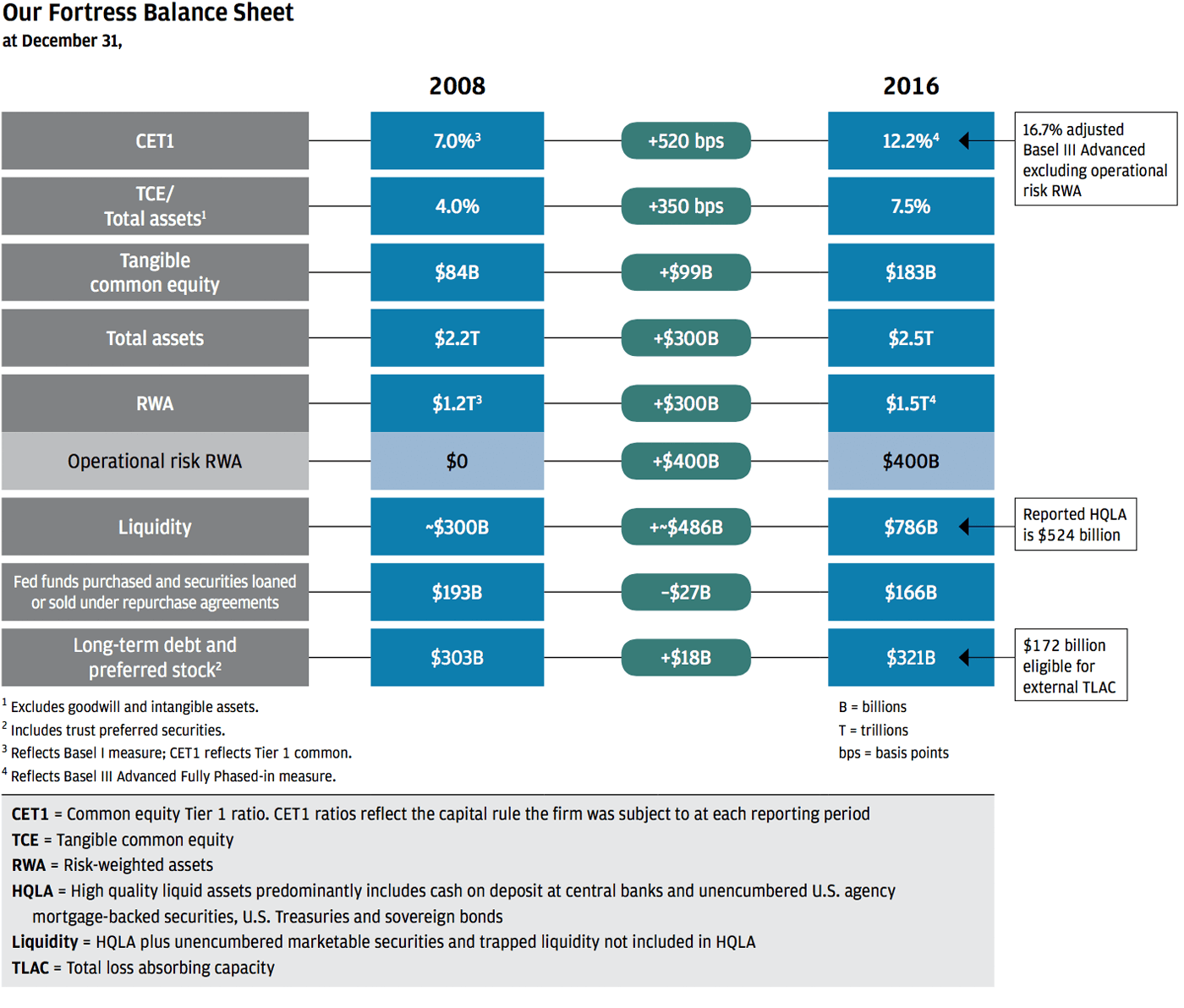

We have a fortress balance sheet – far more than the numbers imply.

The chart above shows the dramatic improvement in our capital and liquidity numbers since 2008. Remember, we had enough capital and liquidity in 2008 to easily handle the crisis that ensued.

The numbers are even better than they look on the chart for the following reasons:

- In 2008, there was no such thing as operational risk capital (not to say there wasn’t operational risk but just that capital was not applied to it). If you measured our capital ratio on the same basis as in 2008 (that is, on an apples to apples basis), we wouldn’t have just 12.2% today vs. 7% in 2008 – we would have 16.7% today vs. 7% in 2008.

- Since 2008, the regulatory definition of liquidity has been prescribed. Now, only deposits at a central bank, Treasuries and government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (plus a limited amount of sovereign and corporate bonds) count as liquidity. Many securities are not allowed to count as liquidity today – on the theory that they can sustain losses and occasionally become illiquid. While maybe not all 100% of the current value of these securities should apply toward liquidity requirements, they should count for something. If you did combine all of these categories as liquidity, our liquidity at JPMorgan Chase would have gone from $300 billion in 2008 to $786 billion today. And remember, our deposits – theoretically subject to “run on the bank” risk – total $1.4 trillion. Even in the Great Recession, the worst case for a bank was only a 30% loss of its deposits.

- Finally, when you include long-term debt and preferred stock as loss absorbing capital,

our total

capital2footnote is approximately $500 billion vs. true risk-weighted assets of $1.1 trillionfootnote3. Essentially, since 2008, our total capital has gone from $387 billion to $500 billion, while actual risk-weighted assets have declined to $1.1 trillion.

In addition to our fortress balance sheet, we are well-diversified, and we have healthy margins and strong controls. These are all factors that dramatically improve safety and soundness, but they are not included in any measures. As you will see below, we can handle almost any stress.

We believe in stress testing, but it could be improved and simplified.

As you know, the Fed puts our company through one “severely adverse” stress test annually, which determines how we can use our capital, pay dividends, buy back stock and expand. We are great believers in stress testing but would like to make the following points:

- Our shareholders should know that we don’t rely on one stress test a year – we conduct more than 200 each week across all of our riskiest exposures. We meet weekly; we analyze each exposure in multiple ways; we are extremely risk conscious.

- The Federal Reserve’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) stress test estimates what our losses would be through a severely adverse event lasting over nine quarters, which approximates the severity and time of the Great Recession; e.g., high unemployment, counterparty failures, etc. The Fed estimates that in such a scenario, we would lose $31 billion over the ensuing nine quarters, which is easily manageable by JPMorgan Chase’s capital base. My own view is that we would make money in almost every quarter in that type of environment, and this is supported by our having earned approximately $30 billion pre-tax over the course of the nine quarters during the real financial crisis.

We don’t completely understand the Fed’s assumptions and models – the Fed does not share them with us (we hope there will be more transparency and clarity in the future). But we do understand that the Fed’s stress test shows results far worse than our own test because the Fed’s stress test is not a forecast of what you actually think will happen. Instead, it appropriately makes additional assumptions about a company’s likelihood to fail – that its trading losses will be far worse than expected, etc. The Fed wants to make sure the bank has enough capital if just about everything goes wrong.

Finally, while we firmly believe banks should have a proper assessment of their qualitative abilities, this should not be part of a once-a-year stress test. Instead, it should be part of the Fed’s regular exam process. The Fed and the banks should work together to continuously improve the quality of their processes while creating a consistent, safe and economy-growing use of capital.

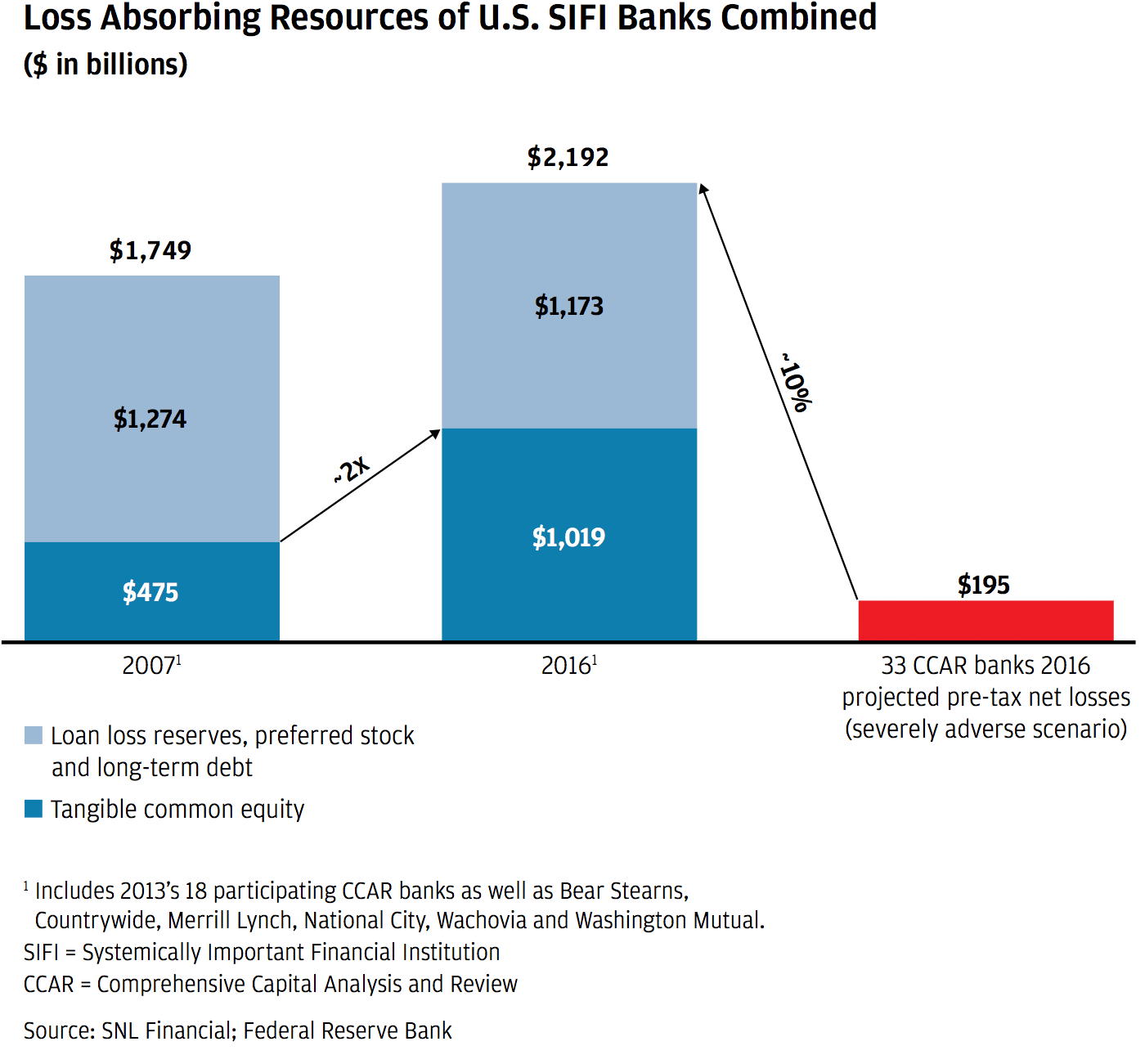

It is clear that the banks have too much capital.

Here is another critical point: The Fed’s stress test of the 33 major banks estimates what each bank would lose assuming it were the worst bank in the crisis, which, of course, will not be true in the real world. But even if that happened, the chart below shows that if you combine all the banks’ extreme losses, the total losses add up to less than 10% of the banks’ combined capital. This definitively proves that there is excess capital in the system.

And more of that capital can be safely used to finance the economy.

Proper calibration of capital is critical to ensure not only that the system is safe and sound but that banks can use their capital to finance the economy. And we think it’s clear that banks can use more of their capital to finance the economy without sacrificing safety and soundness. Had they been less afraid of potential CCAR stress losses, banks probably would have been more aggressive in making some small business loans, lower rated middle market loans and near-prime mortgages.

The global systemically important bank (GSIB) and supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) rules need to be modified.

The GSIB capital surcharge forces large banks to add even more capital, based on some very complex calculations that are highly flawed and not risk based. In fact, the rules often penalize fairly risk-free activity, such as deposits held at the Fed and short-term secured financing. Likewise, the SLR rules force capital to be held on deposit at the Fed in Treasury securities and in other liquid securities. Neither calculation gives credit for operating margins, diversification or annuity streams of business. These calculations should, at a minimum, be significantly modified and balanced to promote lending and other policy goals, including maintaining deep and liquid capital markets, clearing derivatives and directing more private capital in the mortgage market.

Operational risk capital should be significantly modified, if not eliminated.

No one could credibly argue that there is no such thing as operational risk, separate and distinct from credit and market risk. All businesses have operational risk (trucks crash, computers fail, lawsuits happen, etc.), but almost all businesses successfully manage it through their operating earnings and general resources. Basel standards required banks to hold capital for operational risk, and the United States “gold plated” this calculation. Banks in the United States in total now hold approximately $200 billion in operational risk capital. For us, we hold excess operational risk capital which is not being utilized to support our economy. It was an unnecessarily large add-on. If you are going to have operational risk capital, it should be forward looking, fairly calculated, coordinated with other capital rules and consistent with reality. (Currently, if you exit a business that created operational risk capital, you are still, most likely, required to hold the operational risk capital.)

Finally, America should eliminate its “gold plating” of international standards.

American regulators took the new Basel standards across a wide variety of calculations and asked for more. If JPMorgan Chase could use the same international standards as other international banks, it would free up a material amount of capital. The removal of the GSIB surcharge “gold plating” alone would free up $15 billion of equity capital – an amount that could support almost $190 billion of loans. In addition, America gold plated operational risk capital, liquidity rules, SLR rules and TLAC rules. Later in this letter, we will discuss international standards.

Properly done and improved, modifying many of these regulatory standards could help finance the growth of the American economy without damaging the safety and soundness of the system.

3. How do certain regulatory policies impact money markets?

Different from most banks, money center banks help large institutions – including governments, investors and large money market funds – move short-term funds around the system to where those funds are needed most. The recipients of these funds include financial institutions (including nonmoney center banks) and corporations that can have large daily needs to invest or borrow. The products that money center banks offer large institutions are predominantly deposits, securities, money market funds and short-term overnight investments called repurchase agreements. These involve enormous flows of funds, which money center banks handle easily, carefully and securely. They are generally match-fundedfootnote4, almost no credit risk is taken, and most lending is done wholly and properly secured by Treasuries or government-guaranteed securities. These transactions represent a large part of JPMorgan Chase’s balance sheet. Because of new rules, capital in many cases must be held on these short-term, virtually riskless activities, and we believe this has caused distortions in the marketplace. For example:

- Swap spreads, for the first time in history, turned negative, which means that corporations need to pay a lot more to hedge their interest rate exposure.

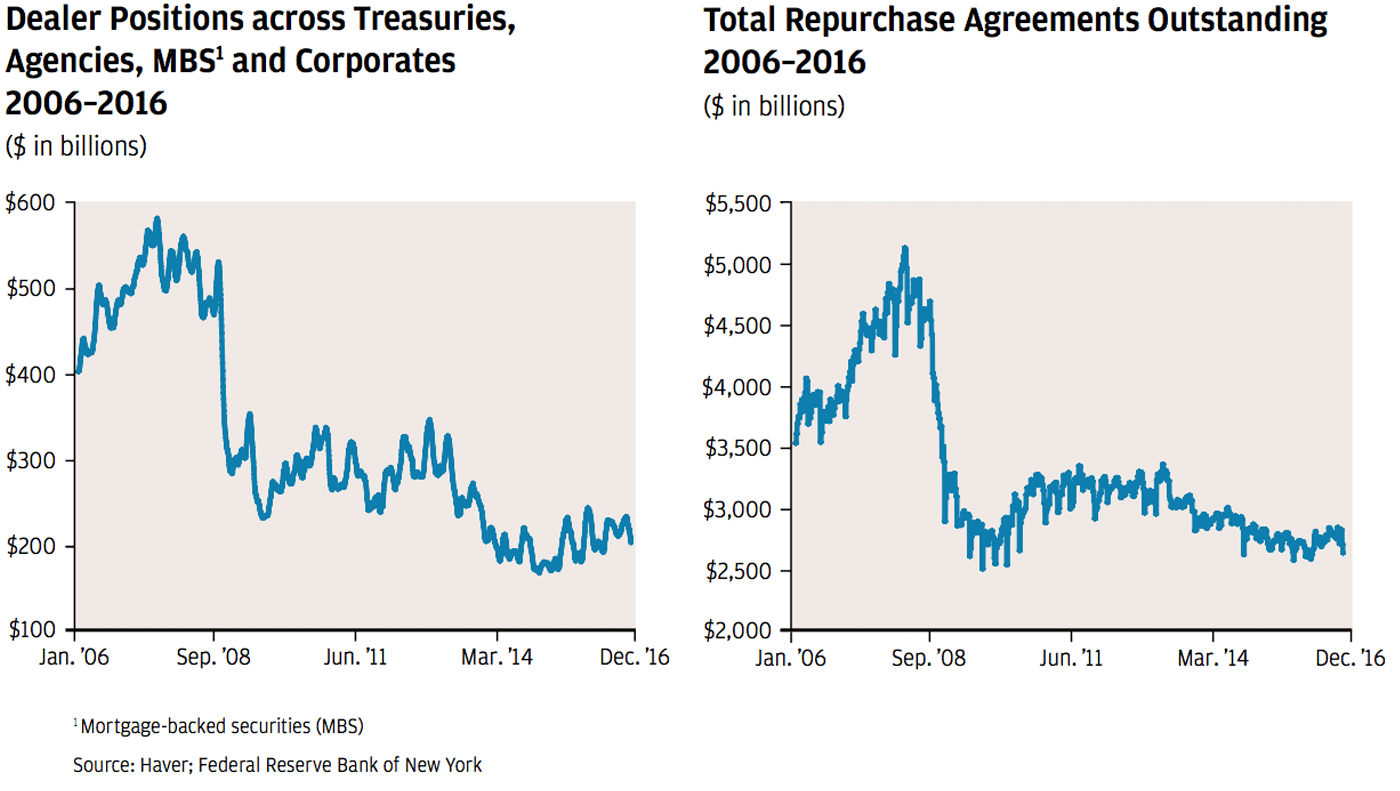

- Reduction in broker-dealer inventories has impacted liquidity.

- Many banks reject certain types of large deposits from some of their large institutional clients. In a peculiar twist of fate – and something difficult for our clients to understand – through 2016, JPMorgan Chase turned away 3,200 large clients and $200 billion of their deposits even though we could have taken them without incurring any risk whatsoever (we simply would have deposited the $200 billion at the central bank).

The chart below shows some of the reduction in banks’ market-making abilities.

We need to work closely with regulators to assess the impact of the new rules on specific markets, the cost and volatility of liquidity, and the potential cost of credit. We should be able to make some modest changes that in no way impact safety and soundness but improve markets.

4. How has regulation affected monetary policy, the flow of bank credit and the growth of the economy?

It is extremely important that we analyze how new capital and liquidity rules affect the creation of credit; i.e., lending. We have yet to see thorough, thoughtful analysis on this subject by economists – because in this case, it is very hard to calculate what might have been counterfactual. However, it seems clear that if banks had been able to use more of their capital and liquidity, they would have been more aggressive in terms of expanding: Think of additional bankers, bank branches and geographies, which likely would have led to additional lending. (On the following pages, we make it clear that this would have been the case in mortgage lending.)

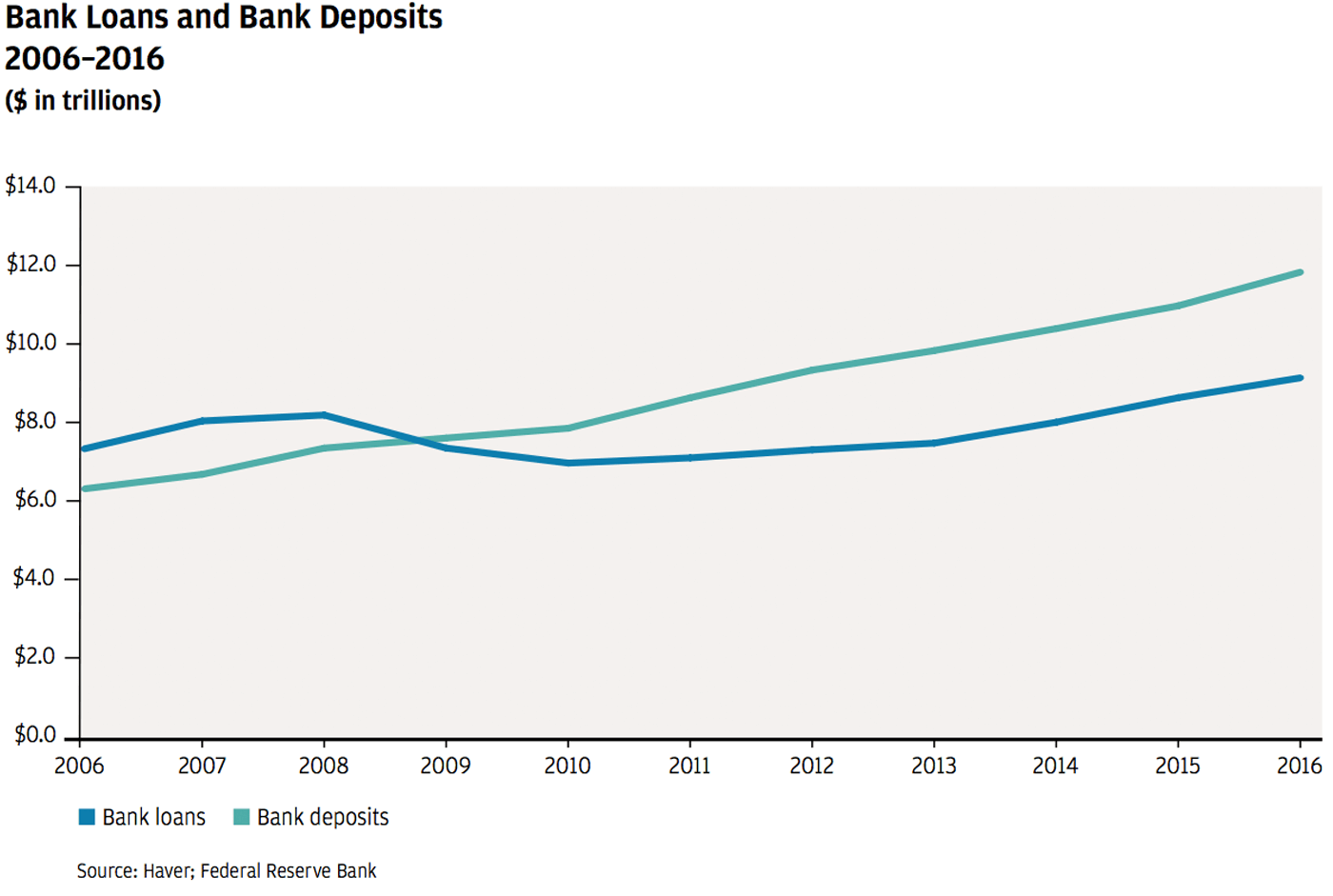

I would like to focus on how liquidity policies may have impacted the effectiveness of monetary policy and lending. The chart below shows bank loans vs. bank deposits from 2006 to 2016. During the last several decades, deposits and loans were mostly balanced. You can see that stopped being true after the start of the Great Recession. Today, loans are approximately $2 trillion less than deposits.

Many factors may influence this scenario, but there are two arguments at the bookends about why this happened:

- There was simply not enough loan demand due to a slow-growing economy.

- The new liquidity rules require banks to hold approximately $2 trillion at the Federal Reserve, whether or not there is loan demand.

It is evident that banks reduced certain types of lending legitimately – think of some of the inappropriate subprime mortgage lending – but banks cut back on other types of lending as well because of the new rules; for example, small business lending due to CCAR and cross-border lending because of GSIB. The ensuing discussion shows how other regulatory rules dramatically decreased mortgage lending, again slowing down the economy.

It is clear that the transmission of monetary policy is different today from what it was in the past because of new capital and liquidity rules. What is not clear is how much these rules reduced lending. Again, working together, we should be able to figure it out and make appropriate improvements that enhance economic growth without damaging the safety of the system.

5. How can we reform mortgage markets to give qualified borrowers access to the credit they need?

Much of what we consider good in America – a good job, stability and community involvement – is represented in the achievement of homeownership. Owning a home is still the embodiment of the American Dream, and it is commonly the most important asset that most families have.

So it is no surprise the financial crisis, which was caused in part by poor mortgage lending practices and which caused so much pain for American families and businesses, led to new regulations and enhanced supervision. We needed to create a safer and better functioning mortgage industry. However, our housing sector has been unusually slow to recover, and that may be partly due to restrictions in mortgage credit.

Seven major federal regulators and a long list of state and local regulators have overlapping jurisdiction on mortgage laws and wrote a plethora of new rules and regulations appropriately focused on educating and protecting customers. While some of the rules are beneficial, many were hastily developed and layered upon existing rules without coordination or calibration as to the potential effects.

The result is a complex, highly risky and unpredictable operating environment that exposes lenders and servicers to disproportionate legal liability and materially increases operational risks and costs. These actions resulted in:

- Mortgages that cost the consumer more

- A tightening credit box; i.e., mortgage lenders are less likely to extend credit to borrowers without a strong credit history

- An inhibition of the return of private capital to the housing industry

- The crowding out of resources to improve technology and the customer experience

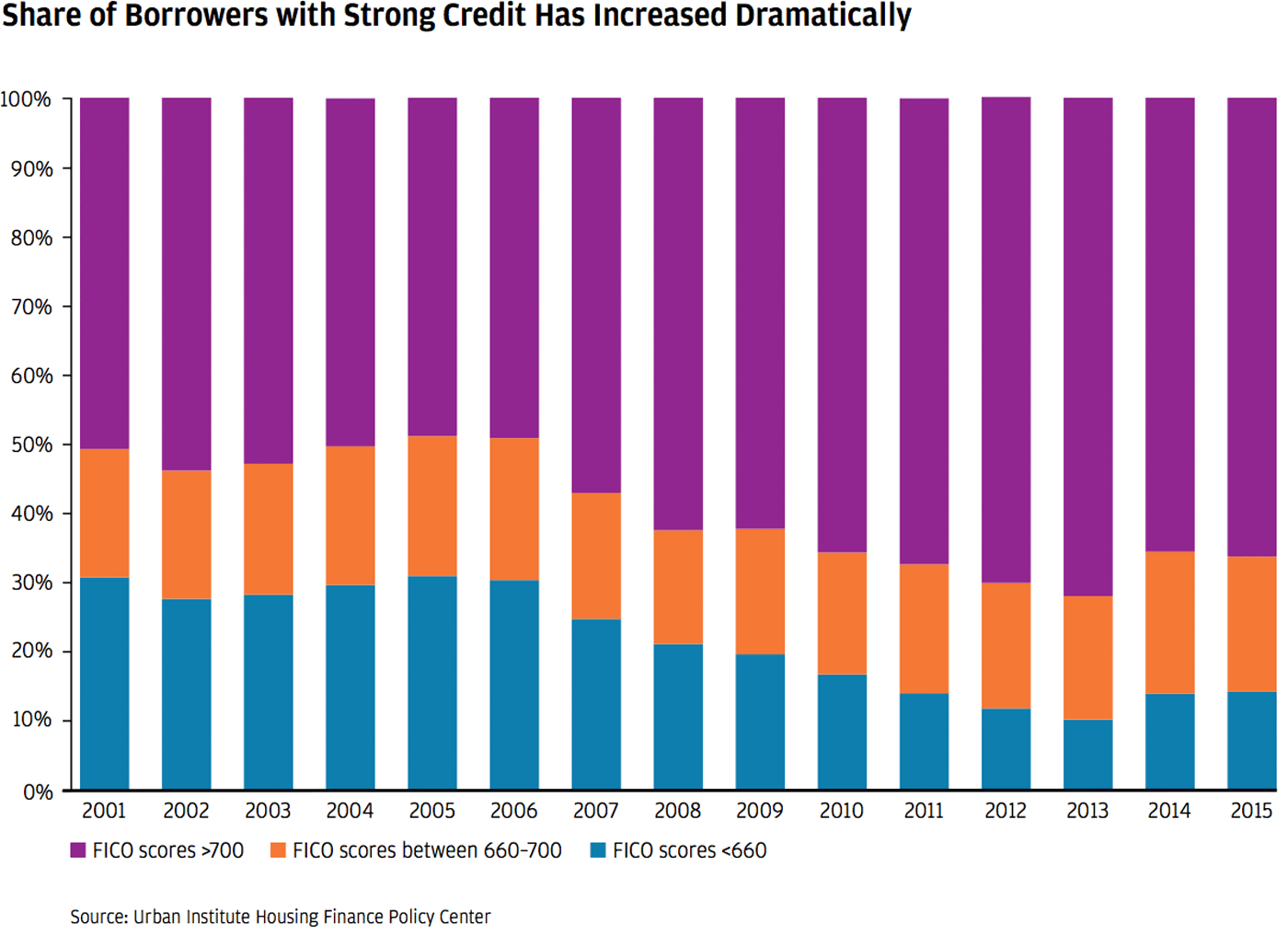

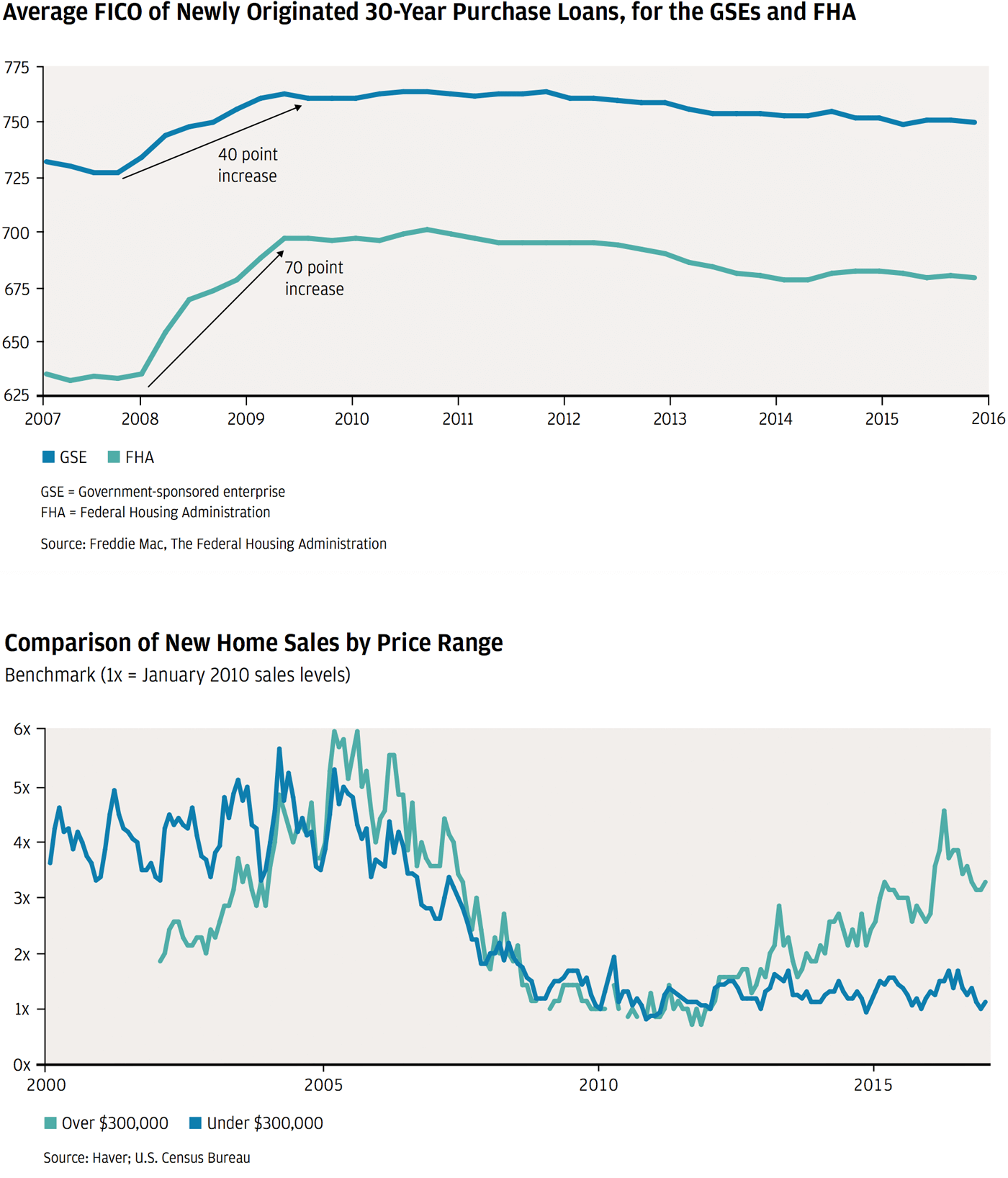

The charts below show the decline in lending to individuals with lower credit scores. The third chart below shows what is likely a related decline in the sales of new but lower priced homes.

There are significant opportunities to make simple changes that can have a dramatic impact on improving the current state of the home lending industry – this will make access to good and affordable mortgages much more achievable for far more Americans. And it’s noteworthy that those who lost access to mortgage credit are the very ones who so many people profess to want to help – e.g., lower income buyers, first-time homebuyers, the self-employed and individuals with prior defaults who deserve another chance.

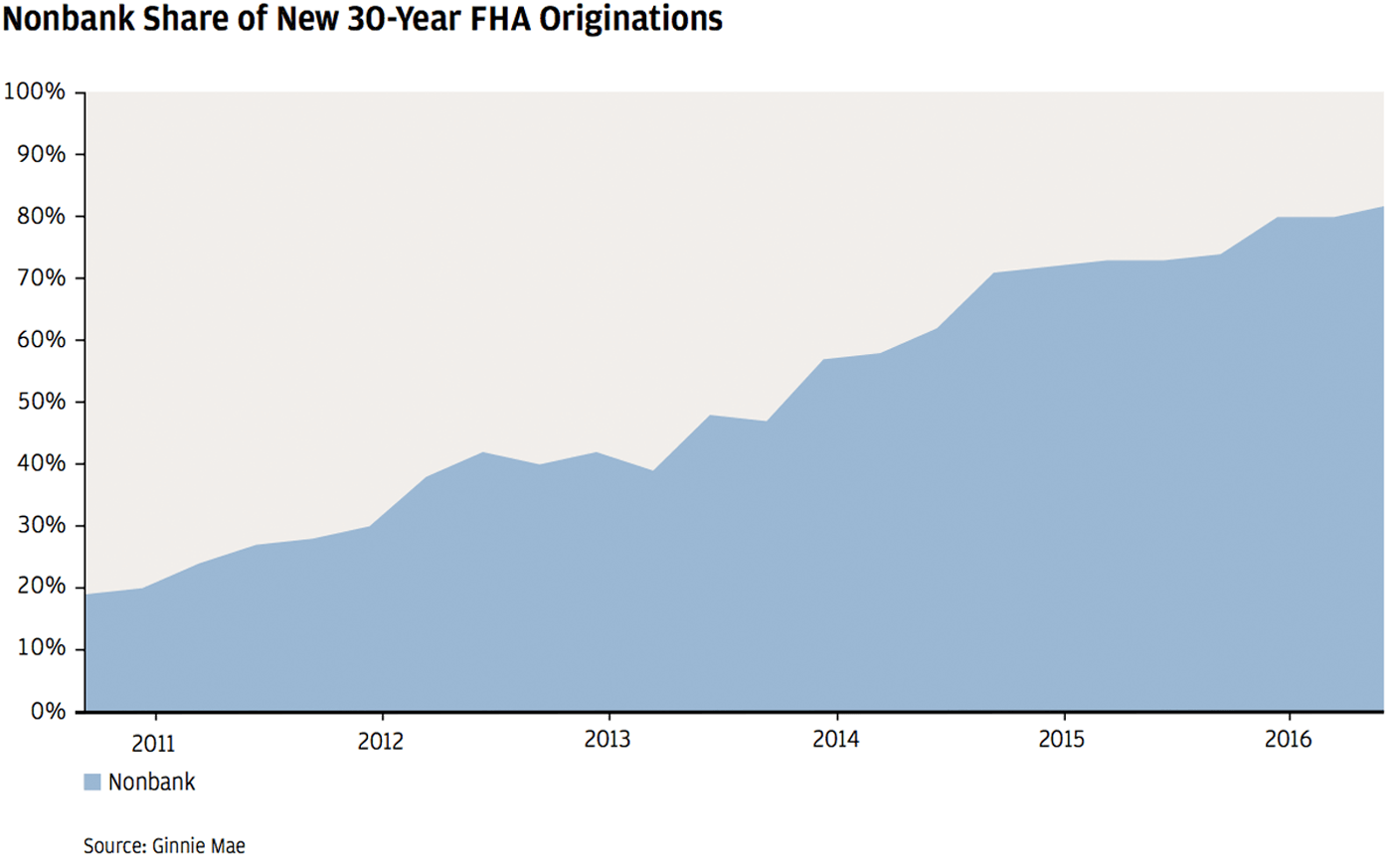

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) reform can bring banks back and expand access to credit.

The FHA plays a significant role in providing credit for first-time, low- to moderate-income and minority homebuyers. However, aggressive use of the False Claims Act (FCA) (a Civil War act passed to protect the government from intentional fraud) and overly complex regulations have made FHA lending risky and cost prohibitive for many banks. In fact, FCA settlements wiped out a decade of FHA profitability, and subsequent losses have kept returns on capital solidly below our target. This has led us to scale back our participation in the FHA lending program in favor of less burdensome lending programs that serve the same consumer base – and we are not alone. The chart below shows that nonbanks have gone from 20% to 80% of FHA originations.

A first step to increasing participation in the FHA program could be the communication of support for only using the FCA, as originally intended, to penalize intentional fraud rather than immaterial or unintentional errors. Other changes that would help would be:

- Improve and fully implement the Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) proposed defect taxonomy, clarifying liability for fraudulent activity.

- Revise certification requirements to make them more commercially reasonable.

- Simplify loss mitigation by allowing streamlined programs and aligning with industry standards.

- Eliminate costly, unnecessary and outdated requirements that make the cost of servicing an FHA loan significantly more expensive than a conventional loan.

Mortgage servicing is too complex: National servicing standards would help.

Mortgage servicing is a particularly complex business in which the cumulative impact of regulations has dramatically increased operational and compliance risk and costs (remember that costs are usually passed on to the customer). Mortgage servicing starts immediately after loan origination (loan origination also has become significantly more expensive and complex as a result of regulatory changes) and involves a continuing and dynamic relationship among a servicer, customer and investor or guarantor, such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac or FHA, to name a few.

New mortgage rules and regulations total more than 14,000 pages and stand about six feet tall. In servicing alone, there are thousands of pages of federal and state servicing rules now – clearly driving up complexity and cost. The Mortgage Bankers Association estimated the fully loaded annual cost of industry servicing, as of 2015, to be $181 for a performing mortgage and $2,386 for a mortgage in default. The cost of servicing a defaulted loan is so high that many servicers avoid underwriting loans that have even a modest probability of default. This is another reason why mortgage companies avoid underwriting certain types of mortgages today than they would have underwritten in the past.

The most promising opportunity in mortgage servicing is to adopt uniform national servicing standards across guarantors, federal and state regulators, and investors. Importantly, there is no need for legislation to implement the necessary coordination to get this done. In particular, the U.S. Treasury is well-positioned to lead key players in the mortgage industry (the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, HUD, the FHA, the Veterans Administration, Ginnie Mae and the U.S. Department of Agriculture) to establish national service standards that would simplify mortgage origination and servicing. Treasury played a similarly pivotal leadership role during the crisis when it helped develop the various mortgage assistance initiatives, such as the loan modification and streamlined refinance programs that allowed many Americans to stay in their homes and communities.

Private capital needs to return in order to make the market less taxpayer dependent — we need to complete the securitization standards.

Private capital in the mortgage industry, particularly in the form of securitizations, dried up as a result of the financial crisis. Eight years later, we still have not opened up a healthy securitization market because of our inability to finalize the rules. Not only does this reduce the share of private capital in the U.S. housing sector (an action that would significantly reduce taxpayer exposure), it also significantly increases the cost to the customer. Taking a few actions would fix this, including:

- Rationalize capital requirements on securitizations to effectively transfer risk to the market while leaving “skin in the game” with the originator.

- Reduce the complexity of data delivery requirements.

- Clarify and define materiality standards associated with compliance with laws and regulations, as well as underwriting standards, to allow for reasonable protections from litigation and to enable standardized due diligence practices.

If we do this right, we believe the mortgage market could add more than $300 billion a year in new purchased loans.

If we take the actions mentioned above, we believe that the cost to a customer would be 20 basis points lower and that mortgage underwriters would be willing to take more – but appropriate – risk on loans (again, this would be for first-time, young and lower income buyers, those with prior delinquencies but who are now in good financial standing and those who are self-employed).

Taken in total, we believe the issues identified above have reduced mortgage lending by more than $300 billion purchased mortgages annually (our analysis deliberately excludes underwriting the subprime and Alt-A mortgages that caused so many problems in the Great Recession). Had we been able to fix these issues five years ago (i.e., three years after the crisis), our analysis shows that, conservatively, more than $1 trillion in mortgage loans might have been made.

If this is true, it may explain why our housing sector has been unusually slow to recover: $1 trillion of new mortgage loans is approximately 3 million loans. Of these, typically more than 20% would go to purchase new homes that would need to be built. By any estimate, this could have had a significant impact on the growth of jobs and gross domestic product (GDP). Our economists think that $1 trillion of loans could have increased GDP, in each of those five years, by 0.5%. In the next section, we will talk about how this is just one of the many things we did to damage our nation’s economy.

6. How can we reduce complexity and create a more coherent regulatory system?

We created a massively complex system in which multiple regulators have overlapping responsibilities on virtually every issue, including rulemaking, examination, auditing and enforcement. This is extremely taxing, complex and overly burdensome for banks, customers of banks and regulators.

Dodd-Frank appropriately established the Financial Services Oversight Committee (FSOC) and assigned to it the responsibility of general oversight across the entire financial system. Unfortunately, the FSOC was not given the ability to adjudicate issues or assign responsibility. Therefore, the FSOC is unable to fully resolve some of the problems that we have detailed in this letter. Finally, another flaw is that some of the laws were written in a way that left them open to broad interpretation and novel enforcement.

There is too much complexity in the system — it could be fixed, and that would make the system stronger.

Nearly everyone agrees there is too much complexity in the current construct of the financial system. A few examples will suffice:

- There are multiple calculations of capital, living wills, the Volcker Rule, etc.

- There are multiple regulators involved independently in rulemaking – just two examples: Seven regulators are involved in setting mortgage regulations, and five regulators oversee the Volcker Rule. This leads to slow rulemaking (e.g., as noted above, we still have not finished the mortgage rules eight years after the crisis), excessive reporting and varied interpretations on what the actual rules are.

- Each agency makes separate audit and reporting demands and can independently take enforcement action on the same subject.

This is clearly a dysfunctional structure. The fix is simple – though getting it done may not be:

- The system should be simplified. There should be one primary regulator on any issue, and we should always strive to make things as simple as possible.

- The primary regulator should establish the rules, the reporting requirements, the audit plans and the enforcement action. Other regulators should get involved only if they believe the primary person did a particularly poor job.

- Everything in the regulatory landscape should be reviewed in the context of safety and soundness, cost-benefit analysis and economic growth.

The FSOC is a good idea but needs to be modified to be more effective.

It makes sense for regulators to be continuously reviewing the entire financial system in an effort to make it as safe and sound as possible (think of this as a well-functioning risk committee of a major bank). But the FSOC should be given some authority to assign responsibility, adjudicate disagreements, set deadlines and force the resolution of critical issues. The FSOC could also enforce due consideration of regulations’ costs vs. benefits and the impact on economic growth.

We have great sympathy for, and agree with, the complaints of the community banks. They are struggling to deal with the complexity and cost of meeting these requirements – and we agree these smaller banks should be relieved of many of the requirements.

Enhancing the functionality of the FSOC and providing regulatory relief where appropriate should not be a political issue. The administration is currently conducting a review of the rules and regulations, which are burdensome and duplicative and which may impede economic growth. That process should be as de-politicized as possible. Everyone stands to gain when growth is enabled in a safe and sound manner.

7. How can we harmonize regulations across the globe?

Currently, American regulators have been pushing the Basel Committee – the international forum that is supposed to set international financial regulatory guidelines – to meet the even higher American standards around capital requirements, derivatives rules, risk-weight calculations, stress testing and other requirements. Many other countries around the world are telling Basel that it has gone too far and that it’s time to let the banks focus on healthy lending and growth of the economy. Following are a few principles that we think should guide global regulations and international coordination to increase safety and soundness and foster global growth:

- International regulations should be coherent and generally harmonized around the world – but they don’t need to be exactly the same.

- We should recognize where there are legitimate reasons to do something different. For example, certain types of loans legitimately could draw different risk weighting in various countries based on historical performance, collateral and bankruptcy laws or even culture.

- Cross-border financial rules need to be part of trade negotiations like any other product or service. We know we will be increasingly competing with Chinese banks, and, eventually, we need the U.S. government to make that part of our trade agreement.

- We can acknowledge that the state of affairs in different countries, including in their banks and their economies, may differ and that these differences might warrant idiosyncratic regulatory responses. For example, European banks for eight years have consistently been put in the position of having to raise more and more capital and liquidity or having to reduce their lending capacity. While their capital standards may have been low compared with American standards (particularly in how they calculate risk-weighted assets), this deleveraging has to have hurt the growth of European economies and opportunities for their people. These banks started from a different position (which had been sanctioned by both their regulators and governments years ago), and we agree that these banks should be allowed to do their job. Most of these banks have plenty of total capital. While it might be true that one day they should have more, the moral imperative now is to help their economies grow and to help the people of those countries.

We are completely convinced that if we can rationally change and coordinate many of these rules, banks can do even more to help the economy thrive.

III. Public Policy

Before we talk about some of the critical issues that confront our country, it would be good to count our blessings. Let’s start with a serious assessment of our strengths.

1. The United States of America is truly an exceptional country.

America today is probably stronger than ever before. For example:

- The United States has the world’s strongest military, and this will be the case for decades. We are fortunate to be at peace with our neighbors and to have the protection of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

- As a nation, we have essentially all the food, water and energy we need.

- The United States has among the world’s best universities and hospitals.

- The United States has a generally reliable rule of law and low corruption.

- The government of the United States is the world’s longest surviving democracy, which has been steadfast, resilient and enduring through some very difficult times.

- The people of the United States have a great work ethic and can-do attitude.

- Americans are among the most entrepreneurial and innovative people in the world – from those who work on the factory floors to geniuses like the late Steve Jobs. Improving “things” and increasing productivity are American pastimes. And America still fosters an entrepreneurial culture, which allows risk taking – and acknowledges that it can result in success or failure.

- The United States is home to many of the best, most vibrant businesses on the planet – from small and midsized companies to large, global multinationals.

- The United States has the widest, deepest, most transparent and best financial markets in the world. And I’m not talking about just Wall Street and banks – I include the whole mosaic: venture capital, private equity, asset managers, individual and corporate investors, and public and private capital markets. Our financial markets have been an essential part of the great American business machine.

Very few countries, if any, are as blessed as we are.

2. But it is clear that something is wrong – and it's holding us back.

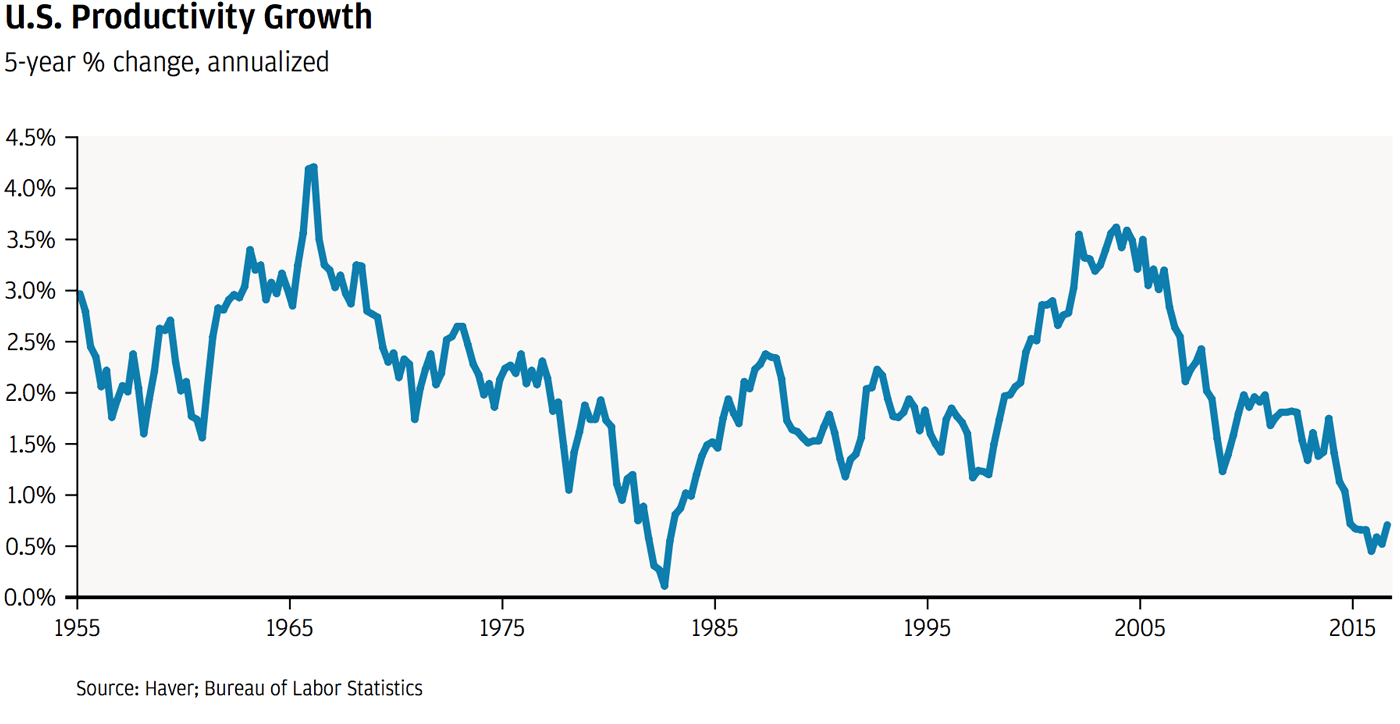

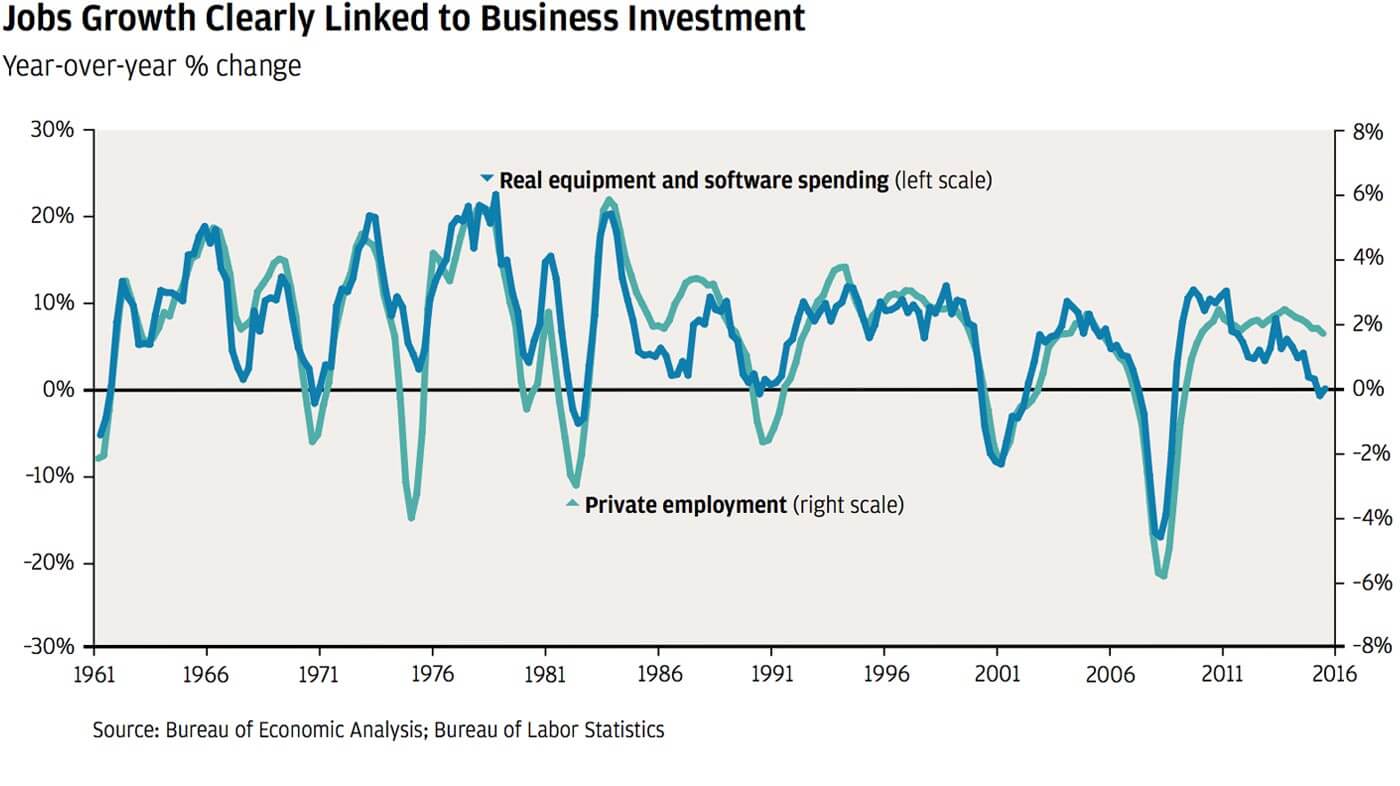

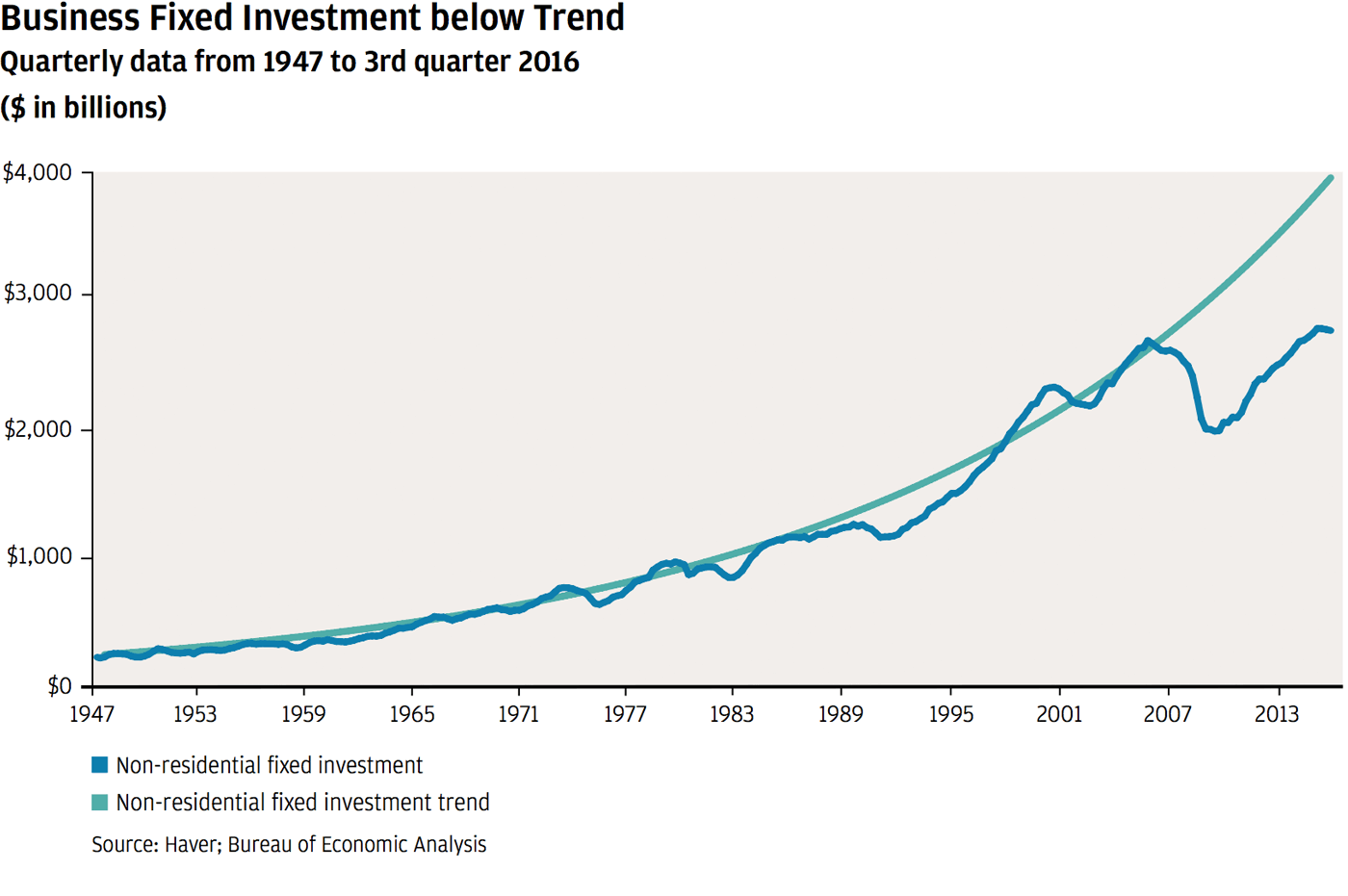

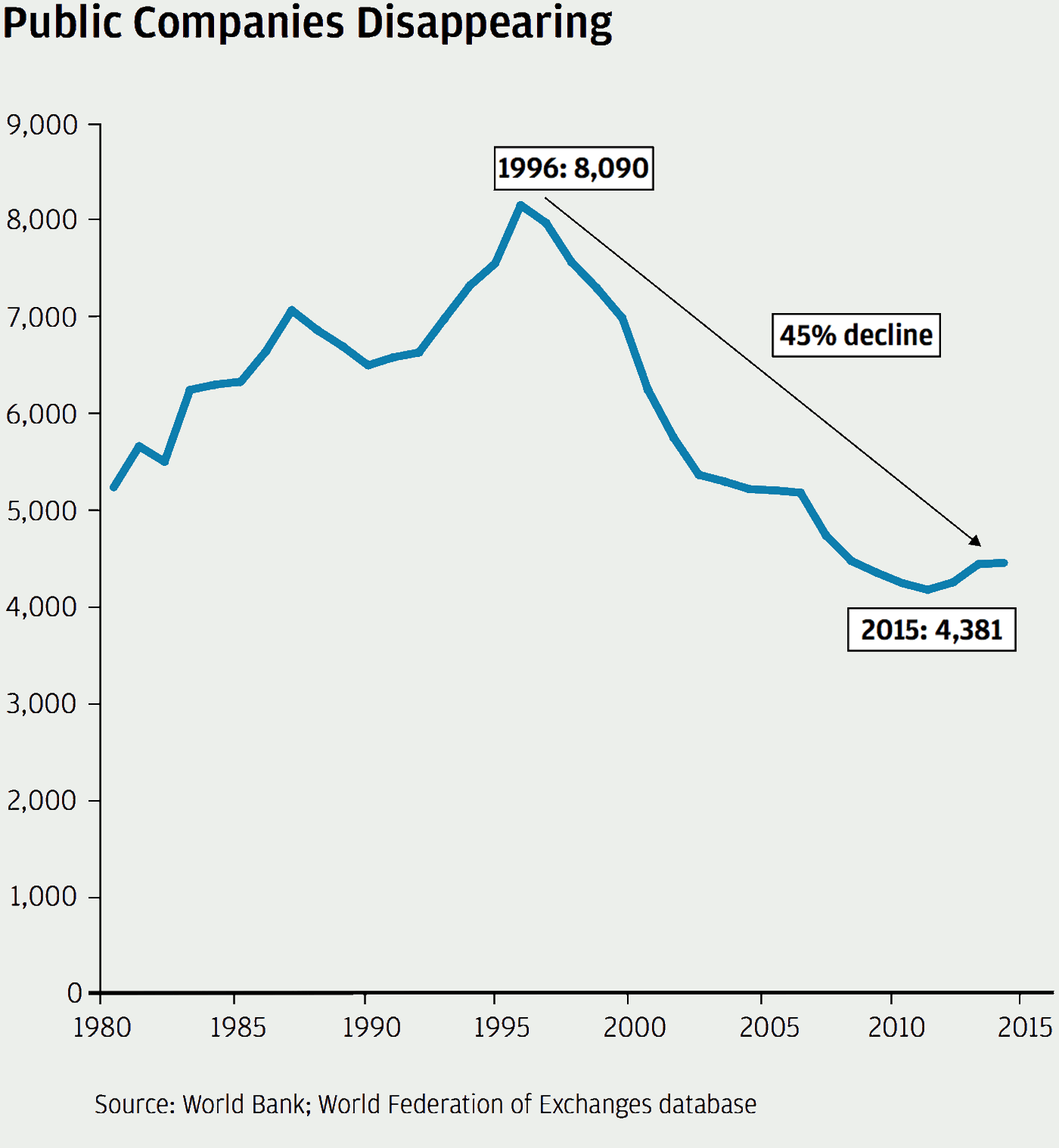

Our economy has been growing much more slowly in the last decade or two than in the 50 years before then. From 1948 to 2000, real per capita GDP grew 2.3%; from 2000 to 2016, it grew 1%. Had it grown at 2.3% instead of 1% in those 17 years, our GDP per capita would be 24%, or more than $12,500 per person higher than it is. U.S. productivity growth tells much the same story, as shown in the chart below.

Our nation’s lower growth has been accompanied by – and may be one of the reasons why – real median household incomes in 2015 were actually 2.5% lower than they were in 1999. In addition, the percentage of middle class households has actually shrunk over time. In 1971, 61% of households were considered middle class, but that percentage was only 50% in 2015. And for those in the bottom 20% of earners – mainly lower skilled workers – the story may be even worse. For this group, real incomes declined by more than 8% between 1999 and 2015. In 1984, 60% of families could afford a modestly priced home. By 2009, that figure fell to about 50%. This drop occurred even though the percentage of U.S. citizens with a high school degree or higher increased from 30% to 50% from 1980 to 2013. Low-skilled labor just doesn’t earn what it used to, which understandably is a source of real frustration for a very meaningful group of people. The income gap between lower skilled and skilled workers has been growing and may be the inevitable consequence of an increasingly sophisticated economy.

Regarding reduced social mobility, researchers have found that the likelihood of workers moving to the top-earning decile from starting positions in the middle of the earnings distribution has declined by approximately 20% since the early 1980s.

Many economists believe we are now permanently relegated to slower growth and lower productivity (they say that secular stagnation is the new normal), but I strongly disagree.

We will describe in the rest of this section many factors that are rarely considered in economic models although they can have an enormous effect on growth and productivity. Making this list was an upsetting exercise, especially since many of our problems have been self-inflicted. That said, it was also a good reminder of how much of this is in our control and how critical it is that we focus on all the levers that could be pulled to help the U.S. economy. We must do this because it will help all Americans.

Many other, often non-economic, factors impact growth and productivity.

Following is a list of some non-economic items that must have had a significant impact on America’s growth:

- Over the last 16 years, we have spent trillions of dollars on wars when we could have been investing that money productively. (I’m not saying that money didn’t need to be spent; but every dollar spent on battle is a dollar that can’t be put to use elsewhere.)

- Since 2010, when the government took over student lending, direct government lending to students has gone from approximately $200 billion to more than $900 billion – creating dramatically increased student defaults and a population that is rightfully angry about how much money they owe, particularly since it reduces their ability to get other credit.

- Our nation’s healthcare costs are essentially twice as much per person vs. most other developed nations.

- It is alarming that approximately 40% (this is an astounding 300,000 students each year) of those who receive advanced degrees in science, technology, engineering and math at American universities are foreign nationals with no legal way of staying here even when many would choose to do so. We are forcing great talent overseas by not allowing these young people to build their dreams here.

- Felony convictions for even minor offenses have led, in part, to 20 million American citizens having a criminal record – and this means they often have a hard time getting a job. (There are six times more felons in the United States than in Canada.)

- The inability to reform mortgage markets has dramatically reduced mortgage availability. We estimate that mortgages alone would have been more than $1 trillion higher had we had healthier mortgage markets. Greater mortgage access would have led to more homebuilding and additional jobs and investments, which also would have driven additional growth.

Any one of these non-economic factors is fairly material in damaging America’s effort to achieve healthy growth. Let’s dig a little bit deeper into six additional unsettling issues that have also limited our growth rate.

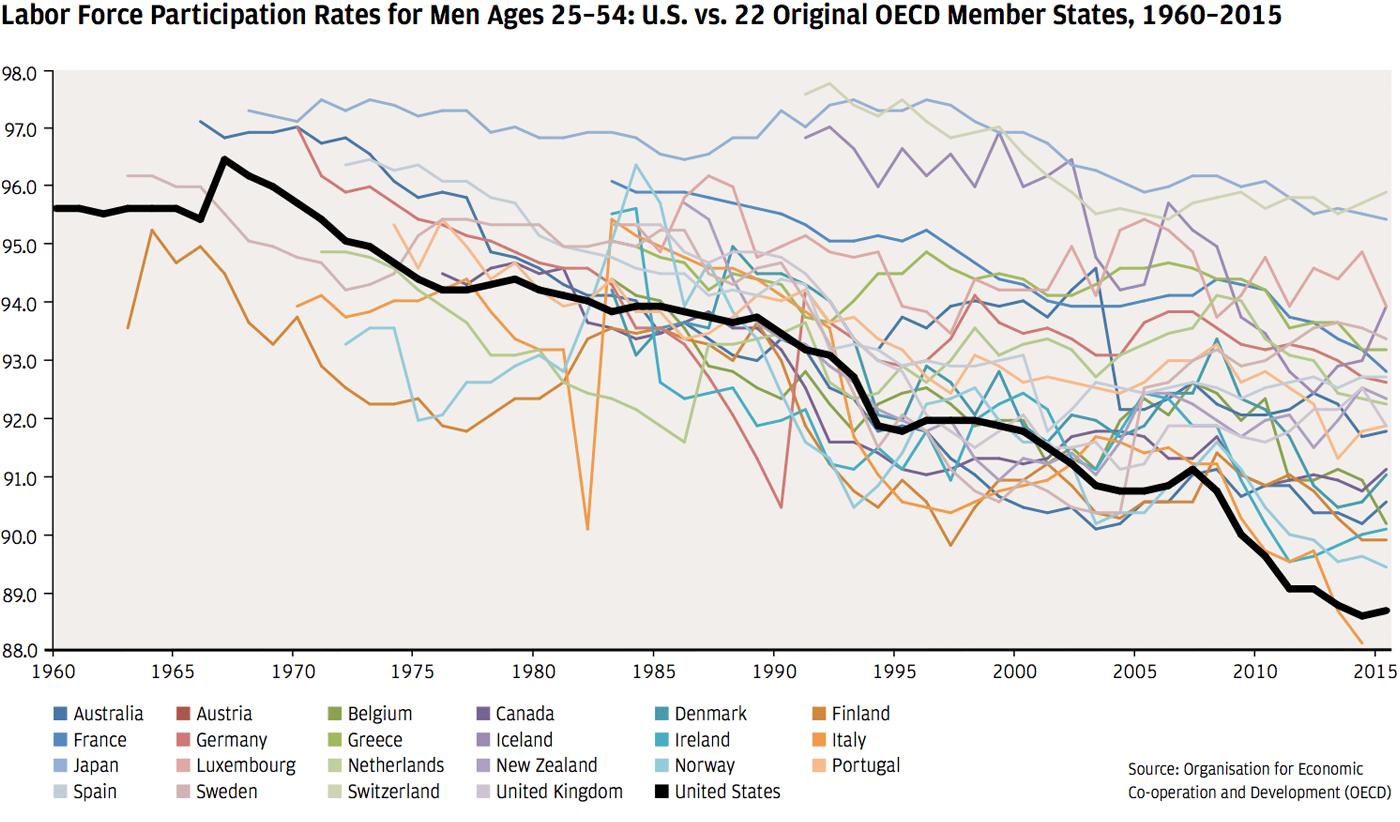

Labor force participation is too low

Labor force participation in the United States has gone from 66% to 63% between 2008 and today. Some of the reasons for this decline are understandable and aren’t too worrisome – for example, an aging population. But if you examine the data more closely and focus just on labor force participation for one key segment; i.e., men ages 25-54, you’ll see that we have a serious problem. The chart below shows that in America, the participation rate for that cohort has gone from 96% in 1968 to a little over 88% today. This is way below labor force participation in almost every other developed nation.

If the work participation rate for this group went back to just 93% – the current average for the other developed nations – approximately 10 million more people would be working in the United States. Some other highly disturbing facts include: Fifty-seven percent of these non-working males are on disability, and fully 71% of today’s youth (ages 17–24) are ineligible for the military due to a lack of proper education (basic reading or writing skills) or health issues (often obesity or diabetes).

Education is leaving too many behind.

Many high schools and vocational schools do not provide the education our students need – the goal should be to graduate and get a decent job. We should be ringing the national alarm bell that inner city schools are failing our children – often minorities and children from lower income households. In many inner city schools, fewer than 60% of students graduate, and many of those who do graduate are not prepared for employment. We are creating generations of citizens who will never have a chance in this land of dreams and opportunity. Unfortunately, it’s self-perpetuating, and we all pay the price. The subpar academic outcomes of America’s minority and low-income children resulted in yearly GDP losses of trillions of dollars, according to McKinsey & Company.

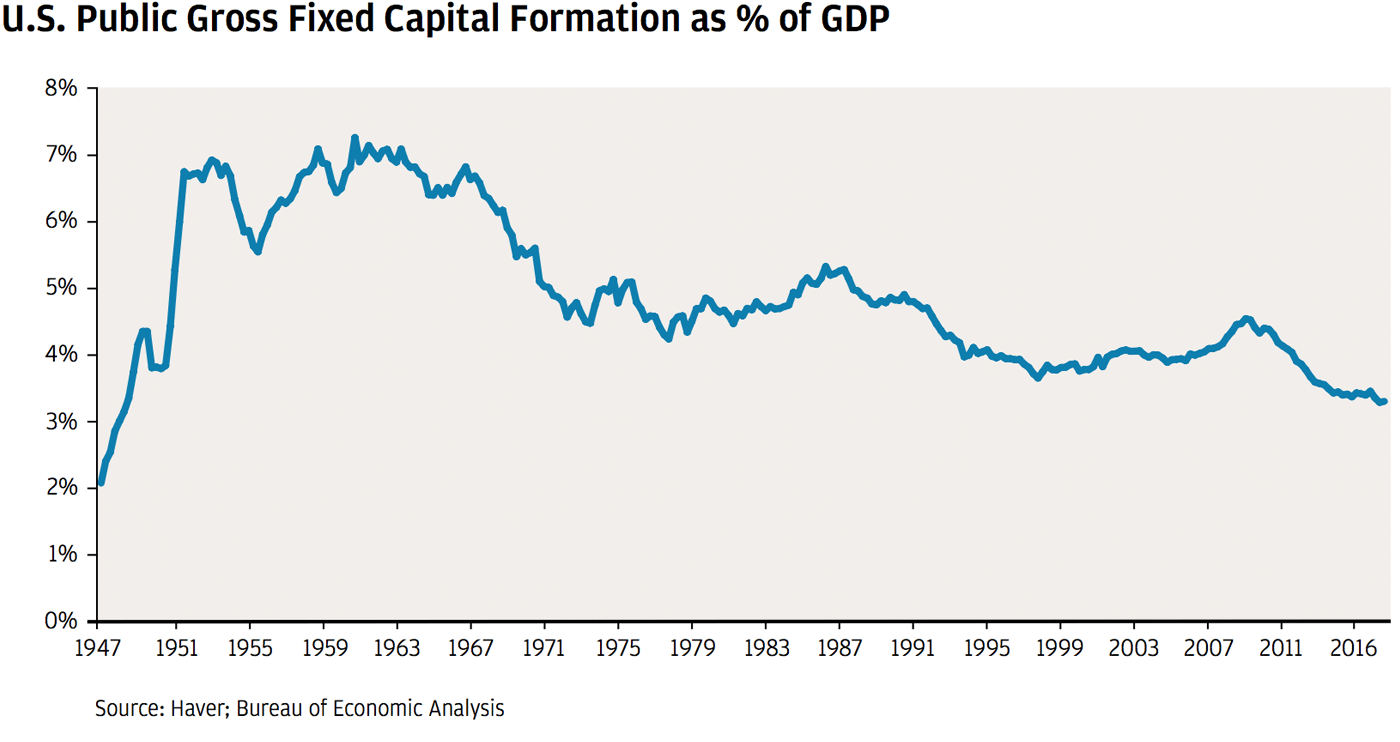

Infrastructure needs planning and investment.